Telling the story of the Spanish Flu in Zurich

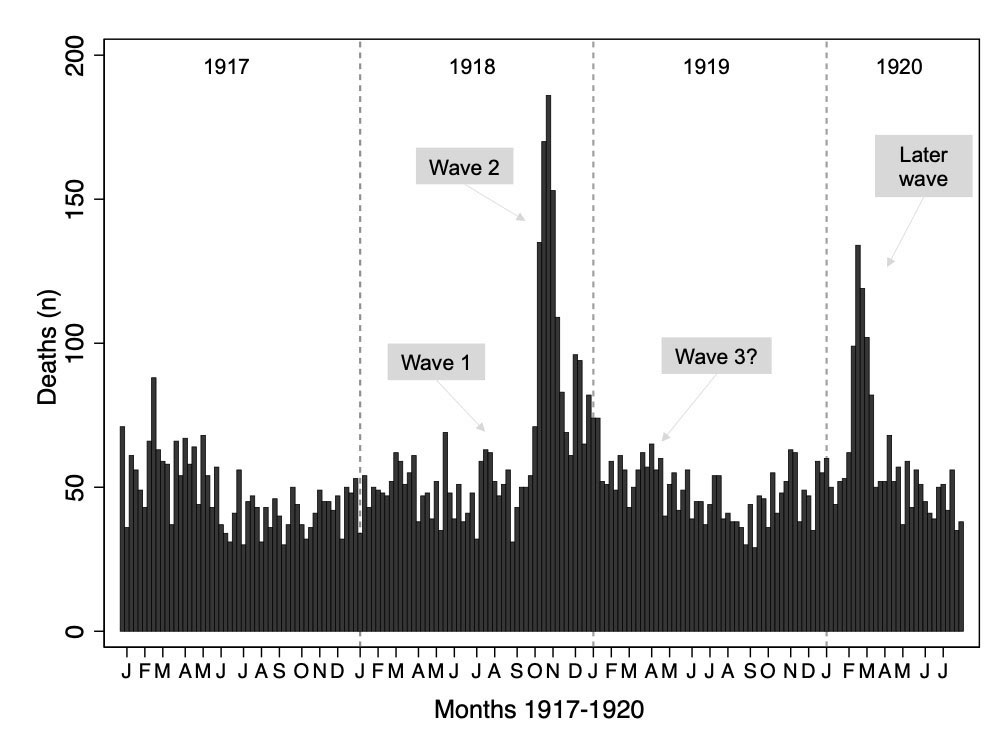

Almost 100,000 cases of flu were reported in the canton of Zurich in 1918 – a number that is roughly equivalent to the present-day population of Winterthur. 2,370 residents of Zurich died of the ‘Spanish flu’ between July and December 1919, more than in any other flu pandemic we know of. A search for traces of the past.

1918 press reports: the flu in the Swiss army

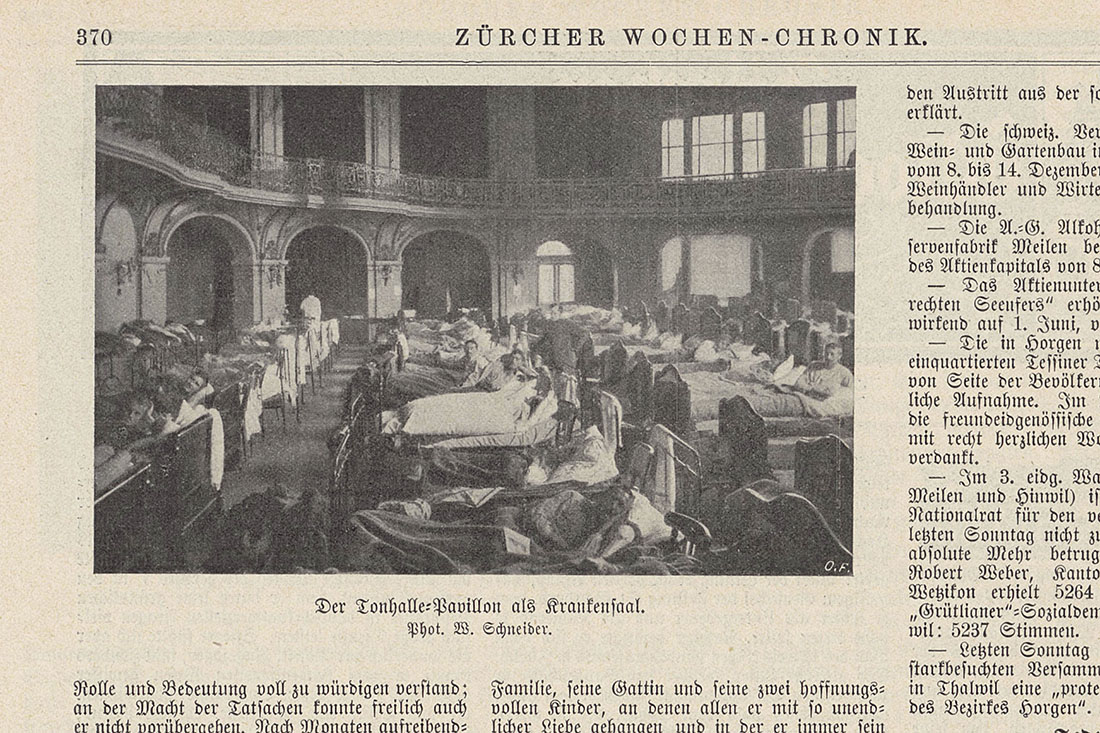

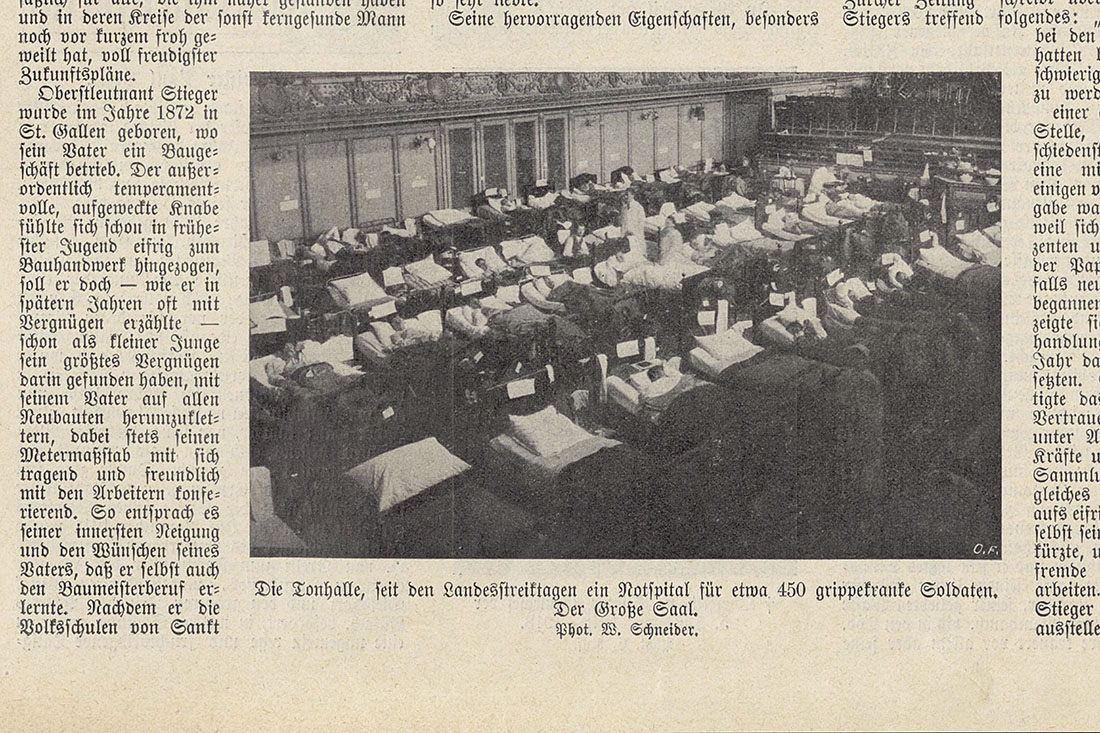

Zurich’s press initially reported on the harmless nature of the mysterious Spanish illness from June to August, before the serious cases of influenza took centre stage. Headline articles were dominated by criticism of the army’s medical service, which were held responsible for the large numbers of unwell soldiers. The soldiers’ quarters were hit by universal shortages, with insufficient transport to move sick soldiers and not enough thermometers.

From September to March, newspapers reported that Switzerland’s economy and health insurance companies had suffered losses in the millions. At the same time, a connection was proposed between the Swiss general strike in November 1918, the deployment of the military ordered by the Federal Council and army command in response, and the flu pandemic. Politicians blamed each other for the flu victims in the army. Amidst the heated atmosphere of the general strike, soldiers who had died from flu attracted attention, with civilian victims garnering less interest.

The media from 2018 to 2022: flu in the civilian population

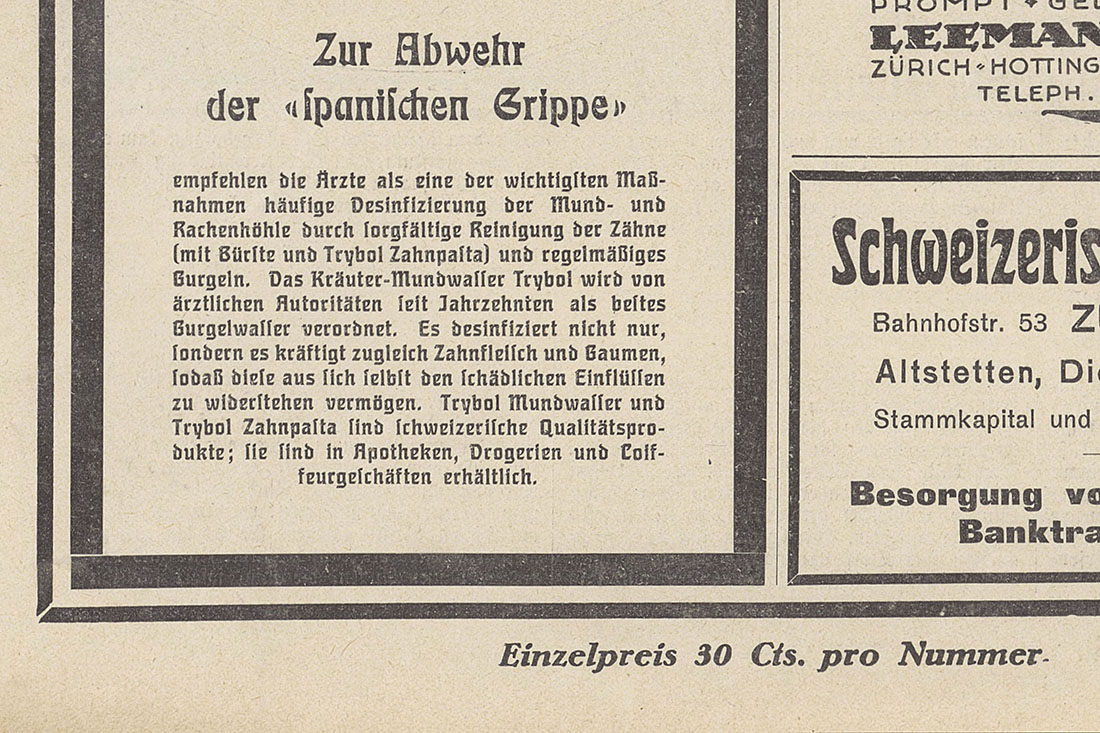

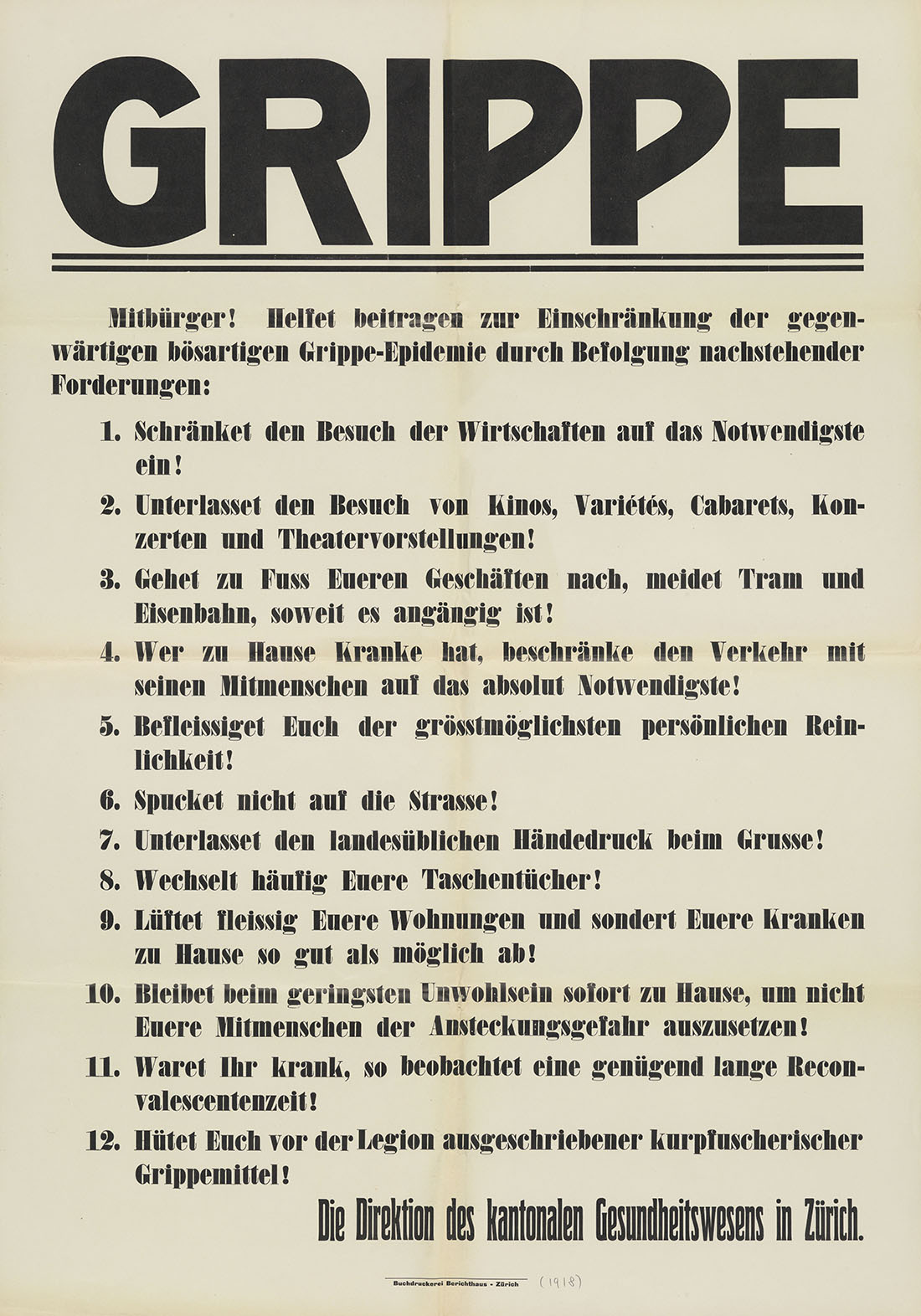

The Spanish flu was the subject of renewed media attention on its 100th anniversary, against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, Zurich’s media emphasised the impact of the Spanish flu on the civilian population: the lack of effective medical support, miracle cures against the flu, family tragedies. On the other, they compared the special shifts worked by nursing staff and the measures taken by the authorities then and now, such as efforts to encourage social distancing or disinfection protocols, like the twice-daily disinfection of Zurich trams with formalin in 1918.

Finally, journalists wondered why Spanish flu hadn’t remained in the collective memory, although large swathes of the population had fallen ill with it. In historiography, the pandemic had long been overshadowed by the First World War and, in Switzerland in particular, by the socio-political impact of the general strike. Compared to a war, the pandemic had no clear start or end point; it had no obvious heroes – just losers. A pandemic also offers an unflinching, painful revelation of weaknesses and inequalities within society, which gives governments little incentive to keep memories of it alive. In addition, the 1918/19 pandemic was difficult to understand: it killed more people than any other flu pandemic, and did so in a horrific way, and yet the symptoms of many sufferers were no worse than those associated with the regular seasonal flu.

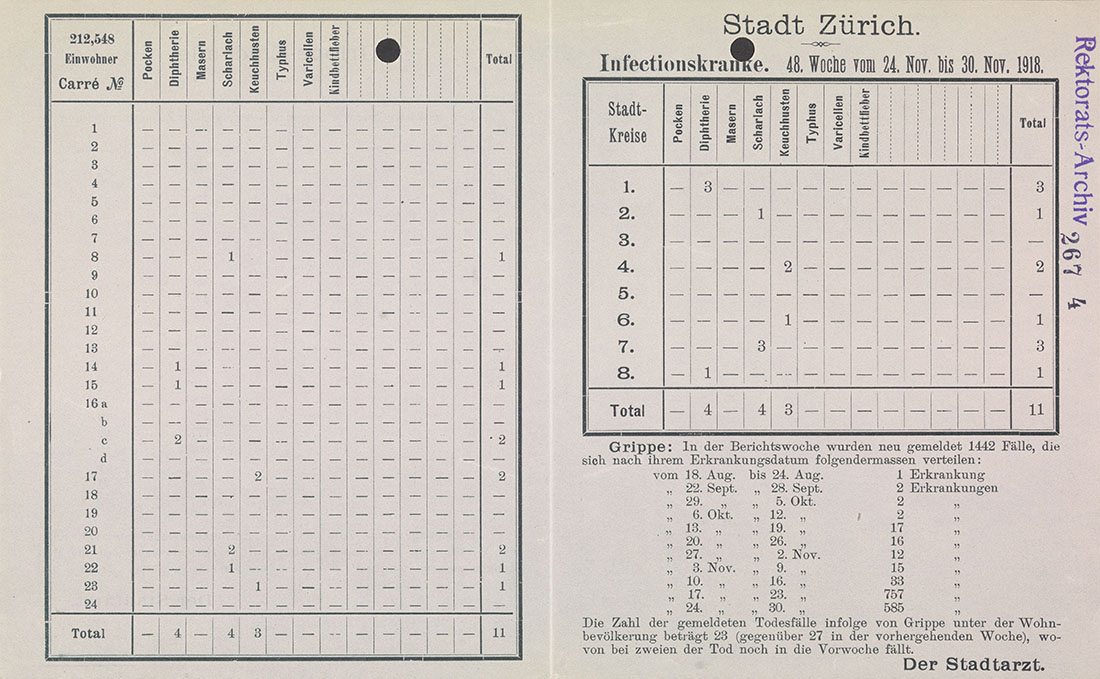

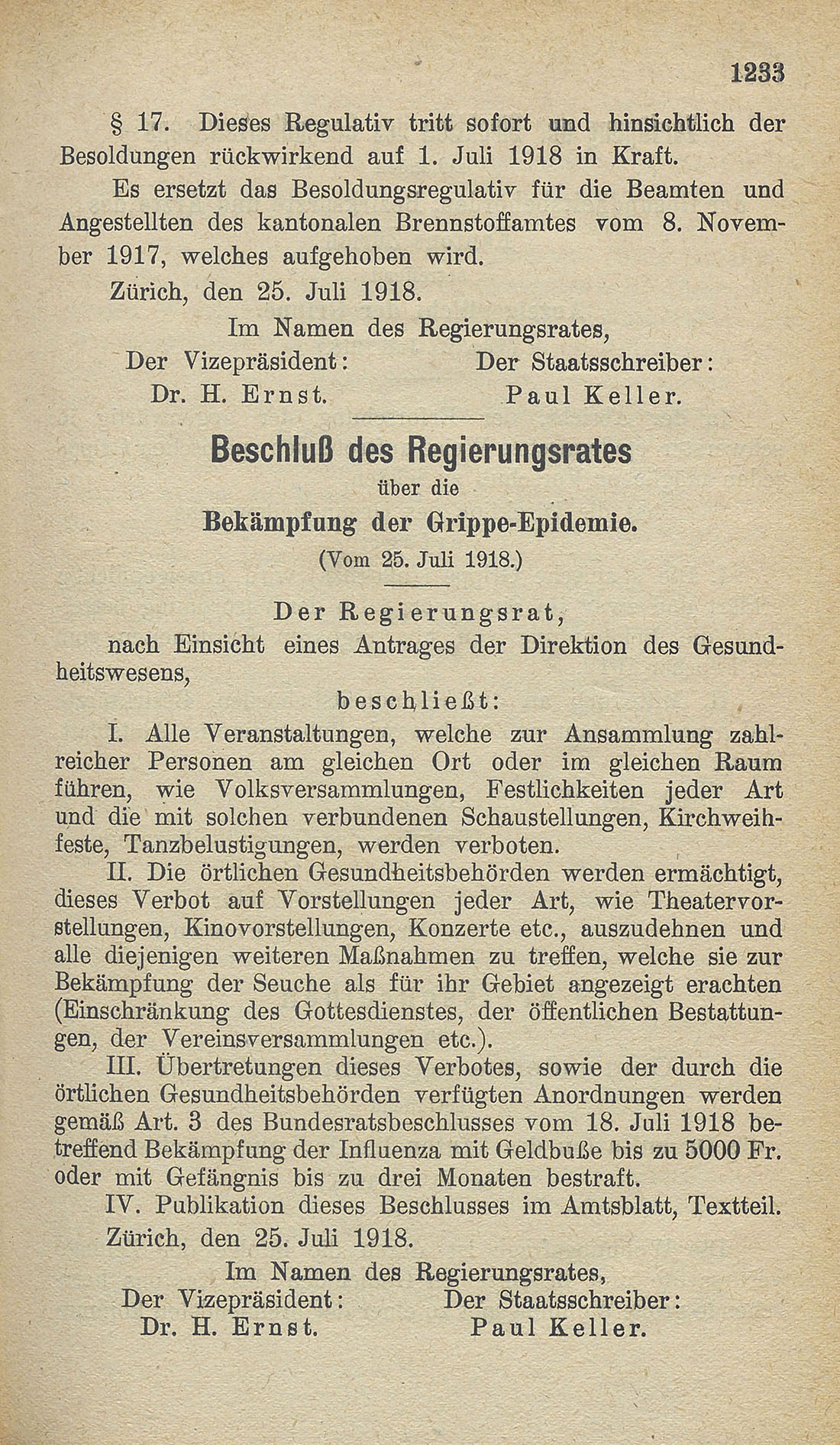

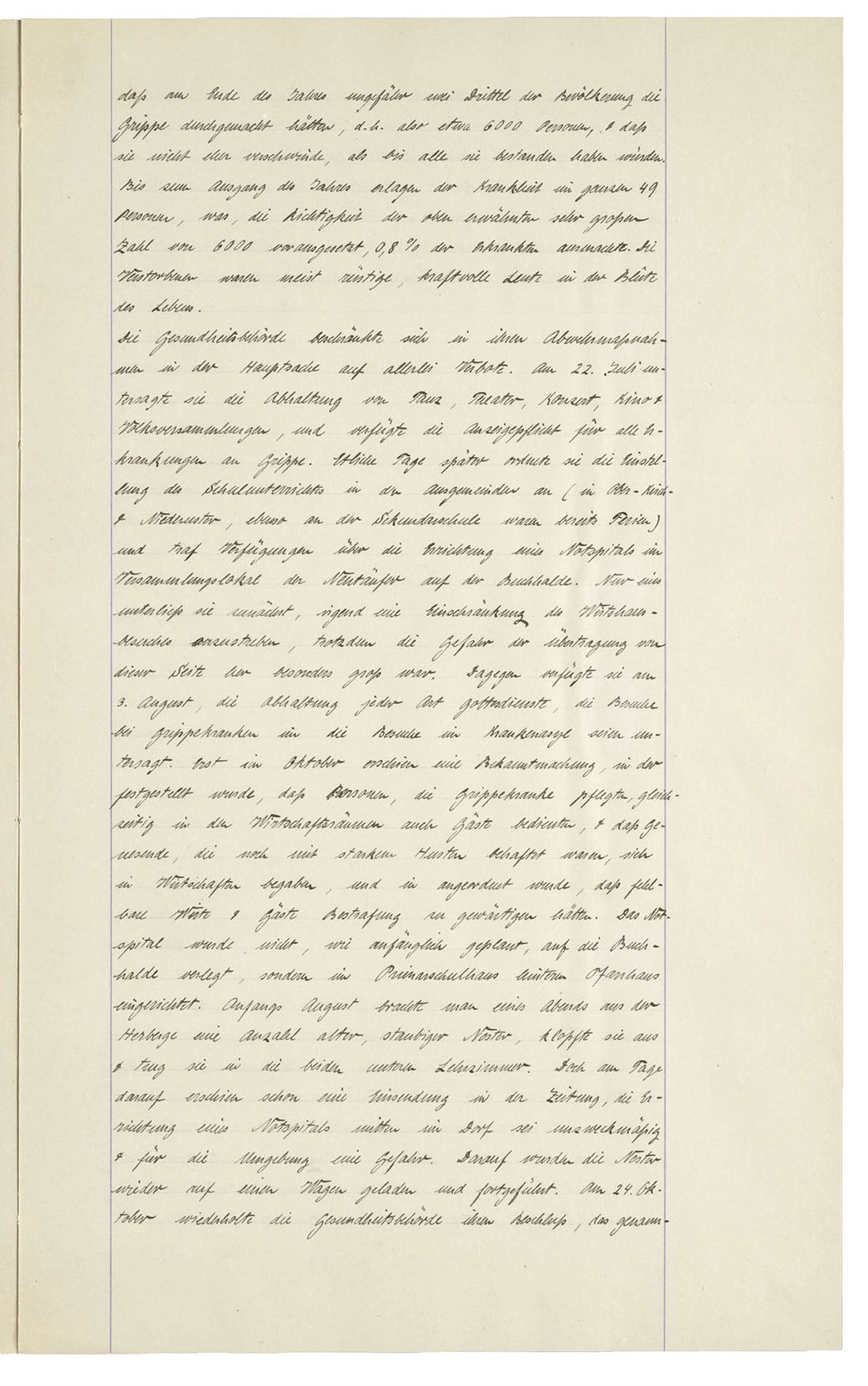

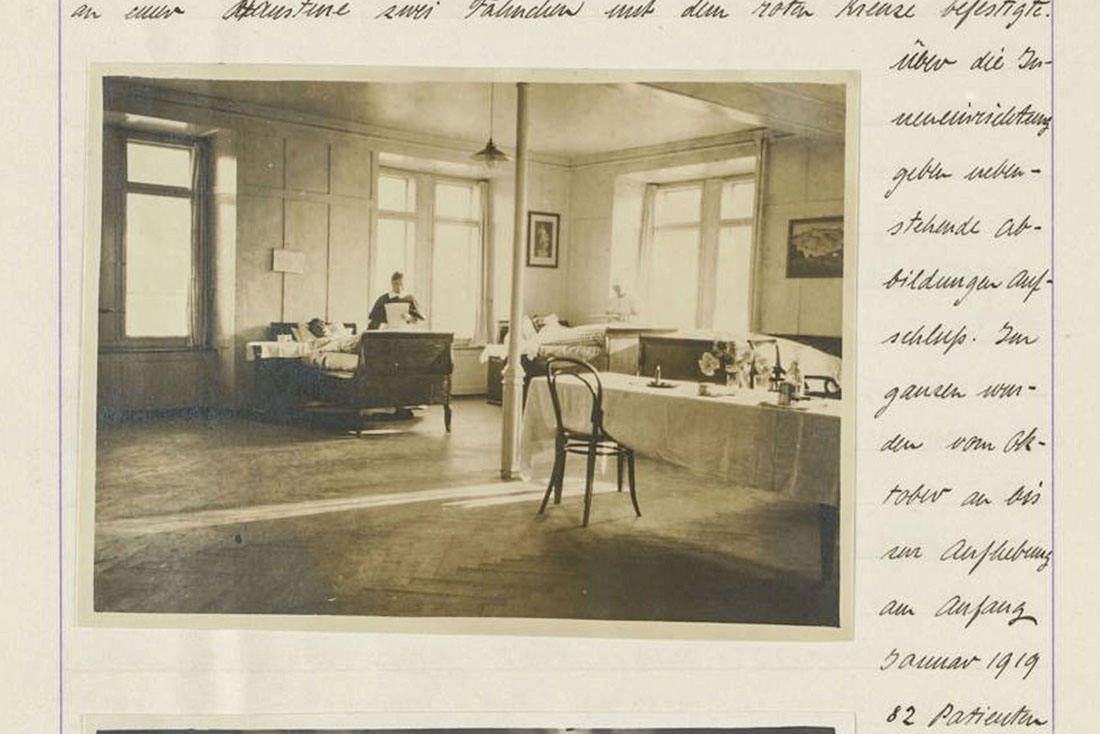

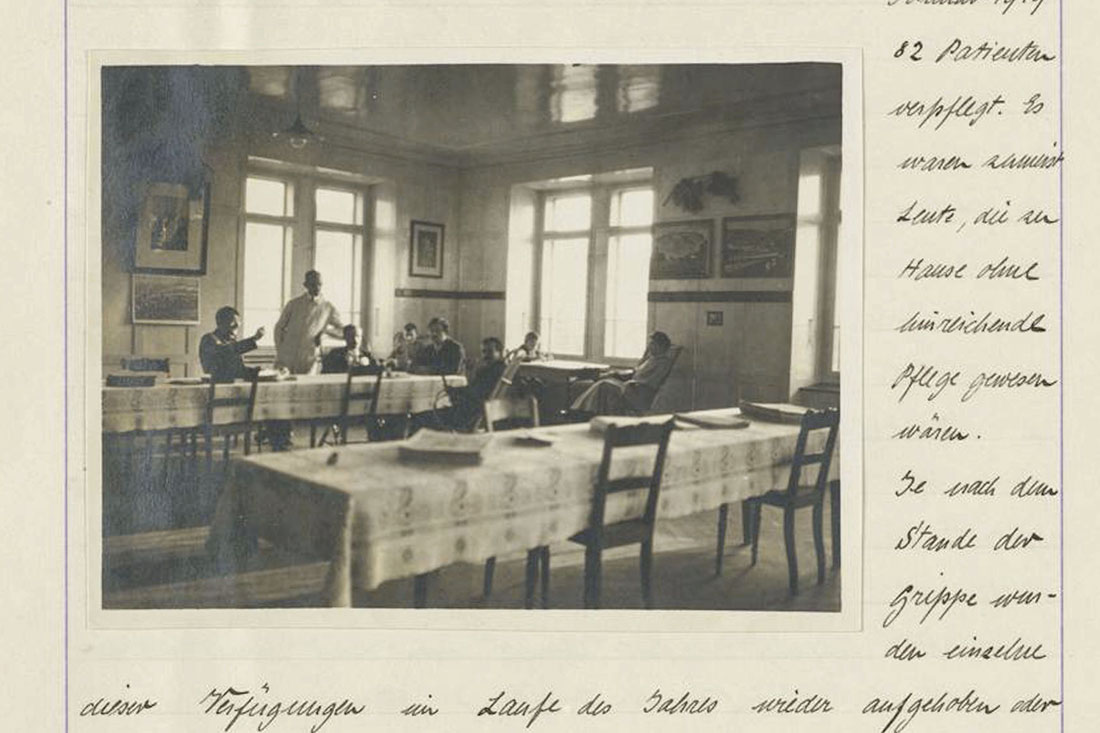

Zurich’s authorities: school closures and a ban on dancing

There was a problem when it came to combating the illness: people did know that flu was a type of illness, but they weren’t yet aware of the influenza virus, the cause of the flu. In addition, flu was not seen as a dangerous illness until 1918. It was only during the Spanish flu that doctors were obliged to report cases of this disease for the first time. On 25 July 1918, Zurich became one of the first cantons to introduce a reporting requirement.

When Zurich’s authorities recognised the severity of the situation, they responded with further measures – some of a drastic nature. School-based teaching was subjected to stringent restrictions, with Zurich city schools forced to wholly or partially suspend operations for nearly three months. In the municipality of Wald, recovered flu victims who no longer had a fever were obliged to avoid any interactions with people outside their family for a further eight days, with particular bans on entering inns and shops. The health authorities of Winterthur banned dances in closed rooms from October to December and instructed restaurants to maintain ‘relaxed’ distances between chairs. Entering inns was never wholly banned in the canton of Zurich, but officials recommended avoiding indoor spaces as far as possible.

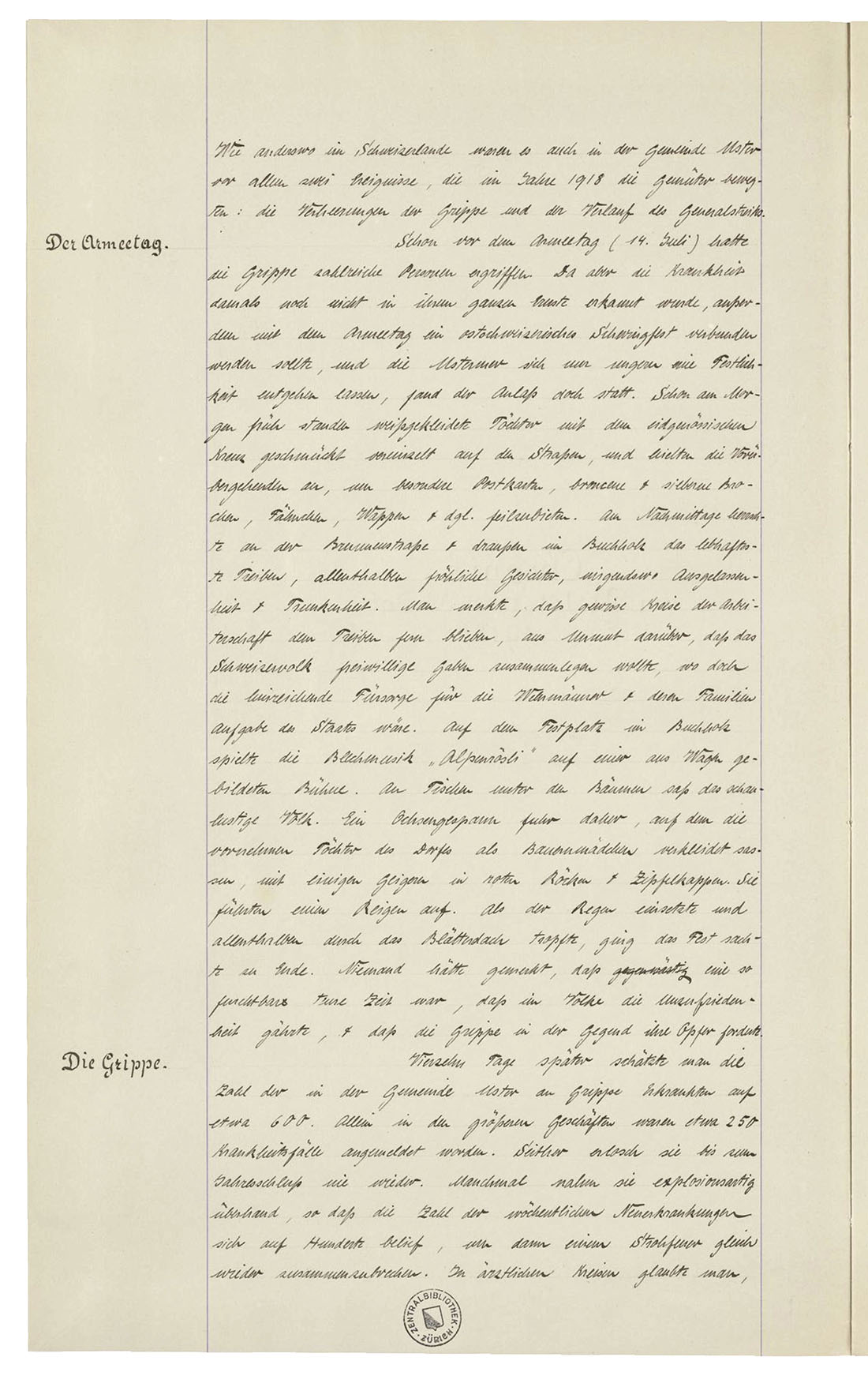

Municipal chronicles: flu ‘in the country’

The Cantonal Statistical Office reported that Zurich and Winterthur were by no means at the peak in terms of relative mortality in 1918. While 23.97 residents out of 1,000 died in the district of Andelfingen and 20.51 in Pfäffikon, these figures were ‘just’ 18.84 and 14.21 in Winterthur and Zurich, respectively. In other words, the Spanish flu did not only make its presence felt in densely-populated areas.

Zurich’s municipal chronicles offer an glimpse into the ramifications of the flu pandemic in rural municipalities. There are reports that ‘daughters of local families’ looked after local soldiers, that the flu ‘in our municipality was relatively mild’ and that the ‘epidemic broke out in October’. Some chroniclers also list the dead. ‘It seems like the writings, ramblings, gossip and fabrications on the flu in the course of the second half of 1918 have covered every possible angle,’ the chronicler of Zollikon criticises, claiming that journalists have been stricken with a ‘wartime flu psychosis’.

The Spanish flu in literature: soldiers’ tales

Authors primarily explored the 1918/19 pandemic in conjunction with the military mobilisation of the period. Meinrad Inglin’s ‘Schweizerspiegel’ [Reflecting Switzerland], for instance, is an epic work exploring the life of a Zurich family. In her novel, she impressively demonstrates how the Spanish flu was initially seen within the army as a trivial, commonplace case of flu, how all the rumours of the dangerous nature of the illness arose and, finally, how one soldier after another began to die from it. The Spanish flu makes a similar appearance in the 1938 edition of ‘Füsilier Wipf’ [Fusilier Wipf] by Robert Faesi.

James Joyce, for his part, published the first version of ‘Hades’, the sixth chapter of his novel ‘Ulysses’, in September 1918 while he was living in Zurich. In this chapter, Leopold Bloom reflects on death, dying and burial: it seems unlikely that Joyce’s own experience of the flu pandemic did not influence this. Finally, Kurt Guggenheim also looks at the Spanish flu in his era-defining novel ‘Alles in Allem’ [All in All], also set in Zurich.

«It was not due to the risk of infection that the public transportation of cadavers was banned, but to hide the scale of the deaths from the populace. Night after night and in secret, the bodies were hardly cold before they were placed in the earth and sprinkled with chlorinated lime. Everything was cancelled: Swiss National Day celebrations, even church services, and schools were closed. As with cholera in its day, only one thing could help: schnapps. And, indeed, those waiting could see how, in the shadow of the sycamore trees, the men passed a bottle among themselves.»

From ‘Alles in allem’ [All in all] by Kurt Guggenheim, pages 493-494.

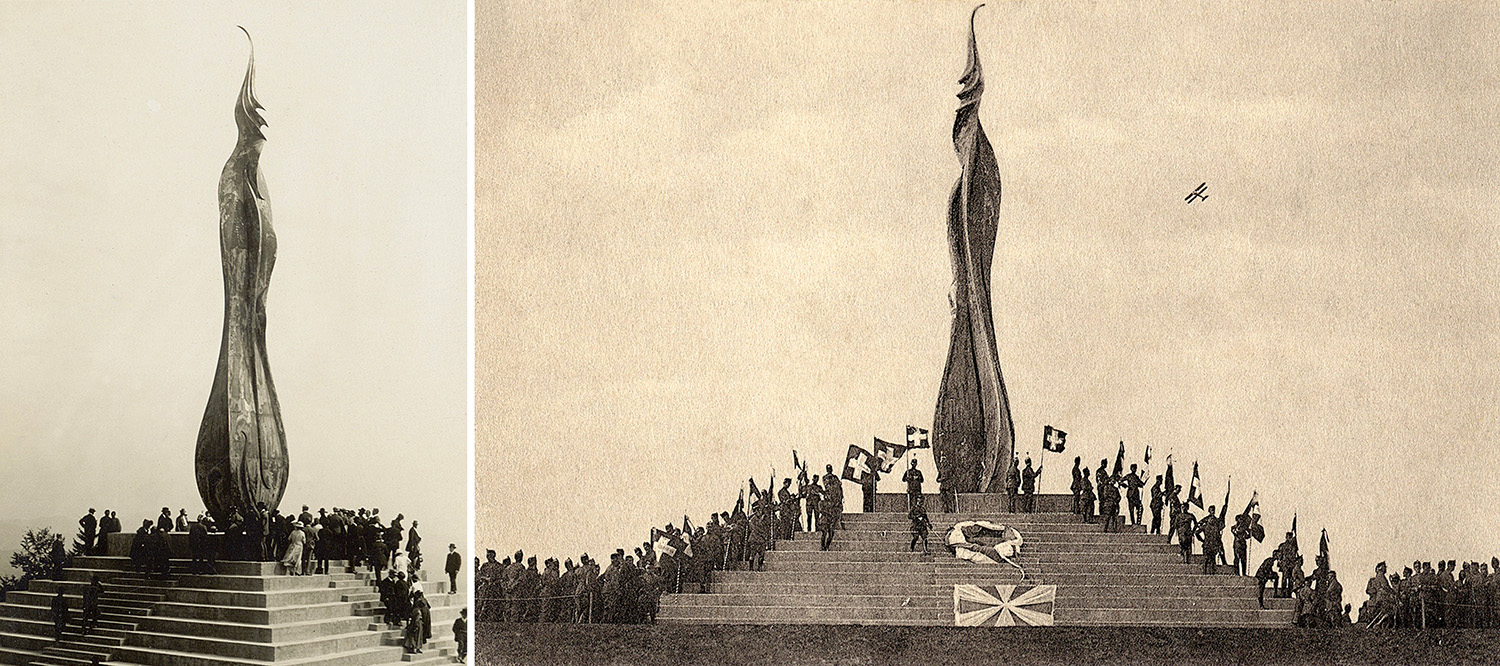

In memory of the victims of the war: flu casualties

After the end of the war, memorial committees were set up in various places across Switzerland, inspired by the memorials in other countries. The Forch memorial started out as an initiative proposed by the NCO association of the canton of Zurich. The memorial committee and Zurich’s government didn’t just want to commemorate the soldiers who died in active service on the border from 1914 to 1918. All military ‘war victims’ up to 1919 were to be taken into account – including, and in particular, the soldiers who had ensured law and order during the general strike and who, as a result, had contracted and died from the flu.

This interpretation of the term ‘war victim’ was a controversial one from the perspective of domestic politics in the immediate wake of the general strike. In addition, it failed to take any civilian flu victims into account. Ultimately, the following inscription was agreed and carved into the stone base of the Forch memorial: ‘THIS MEMORIAL WAS ERECTED BY THE PEOPLE OF ZURICH AS A SYMBOL OF ZURICH’S VICTIMS WHO PROVIDED PROTECTION FOR THE COUNTRY DURING THE 1914–1918 WORLD WAR.’

30,000 to 50,000 people attended its dedication in 1924. Swiss President Robert Haab made mention of the flu dead in his speech: ‘Even though we may have avoided the very worst fate, a great wave of death did indeed pass over our country in autumn 1918; flu caused the demise of innumerable people.’

Research into the flu: a ‘deafening silence’

For a long time, the Spanish flu was seen as the ‘forgotten pandemic’ because it was hardly mentioned in the history books. For instance, no comprehensive work in the field of the history of science has examined the Spanish flu in Zurich: just two unpublished licentiate theses are available. In the medical field, doctor Emil Studer’s 1920 dissertation saw him describe all 2,867 cases of flu from 1918 at the Medical Clinic of Zurich Cantonal Hospital. Since Studer, Hans Thalmann (1968) and Nina Maria Koren (2003) have been the only researchers to write medical dissertations on the flu in Zurich.

More recent research talks of a ‘pandemic gap’: after 1918, there were no major pandemics of illnesses transmitted by droplets. Combined with the ‘deafening silence’ of historians of science and few medical theses in this area, this may have led to the memory of pandemics fading and the risk of a new pandemic being underestimated.

Historians, in turn, ask how people’s experiences of the Second World War shape their perceptions of the First World War, talking of a ‘forgotten war’ in this regard. As a result, Spanish flu has been overshadowed and forgotten in two respects. On the one hand, it is dwarfed by the socio-political upheaval of the First World War and on the other, people’s experiences of the Second World War impacted their view of the First World War. As a result, more modern historical research has called for further investigations to show that the 1918/19 flu pandemic 'was more than an inscrutable annex to Switzerland’s political history between the end of the First World War and the general strike’.

Suggested reading

Nowadays, it is no longer possible to talk of a ‘forgotten pandemic’ in research, neither globally nor for the various regions of Switzerland. If you would like to learn more about the history of the Spanish flu in Switzerland in more detail, the following books and articles represent a good introduction to the various strands of research in this field.

- ‘Heimatfilme und Denkmäler für Grippetote. Geschichtskulturelle Reflexionen zur wirtschaftlichen Nutzbarmachung des Ersten Weltkriegs in der Schweiz’ [Regional films and memorials to the flu dead. Cultural and historical reflections on the economic exploitation of the First World War in Switzerland] by Konrad Kuhn and Béatrice Ziegler in ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung. Public History zwischen Wirtschaft und Wissenschaft’ [Processing the past. Public history between economics and science]

- ‘Das Virus der Unsicherheit. Die Jahrhundertgrippe von 1918/19 und der Landesstreik’ [The virus of uncertainty. The flu of the century in 1918/19 and the general strike] by Patrick Kury in ‘Der Landesstreik. Die Schweiz im November 1918’ [The general strike. Switzerland in November 1918]

- ‘Die Grippeepidemie 1918–1919 in der Schweiz’ [The 1918–1919 flu pandemic in Switzerland] by Christian Sonderegger and Andreas Tscherrig in ‘ “Woche für Woche neue Preisaufschläge”. Nahrungsmittel-, Energie- und Ressourcenkonflikte in der Schweiz des Ersten Weltkrieges’ [‘New price increases week after week’. Food, energy and resource conflicts in Switzerland during the First World War]

- ‘The “Pandemic Gap” in Switzerland across the 20th century and the necessity of increased science communication of past pandemic experiences’ by Kaspar Staub, Frank J. Rühli and Joël Floris in ‘Swiss Medical Weekly’

- ‘Public health interventions, epidemic growth, and regional variation of the 1918 influenza pandemic outbreak in a Swiss canton and its greater regions’ by Kaspar Staub et al. in ‘Annals of Internal Medicine’

- ‘Die Grippeepidemie 1918/19 in Zürich’ [The 1918/19 flu epidemic in Zurich], dissertation by Hans Thalmann, Zurich 1968

- ‘Krankenbesuche verboten! Die Spanische Grippe 1918/19 und die kantonalen Sanitätsbehörden in Basel-Landschaft und Basel-Stadt’ [Visiting the sick prohibited! The Spanish flu of 1918/19 and the cantonal health authorities in Basel-Landschaft and Basel-Stadt] by Andreas Tscherrig

Information on the Spanish flu in Zurich can also be found in the Zurich bibliography.

Dr Joël Floris, historian, Willy Bretscher Fellow 2022/23

June 2023

Header image: historic and current publications exploring Spanish flu. (Image: Stefanie Ehrler/ZB Zürich)

The research was made possible by the 2022/2023 Willy Bretscher Fellowship.