Zurich is building a house for art...

…and has been for quite some time. More than a century separates the opening of the first building on Heimplatz from the completion of the new extension. Many things have changed during that period.

A new gateway to art is opening up

The extension to Zurich’s Kunsthaus is soon to be inaugurated. The timing is perfect: we are living in an age in which art has become increasingly important.

Sir David Chipperfield’s construction reflects that fact. Yet it did not come about overnight: it has been 20 years in the planning. The vision of a “New Kunsthaus” came with a master plan and business plan. This was a prudent move: with an investment of this size that will permanently transform a neighbourhood in the heart of the city, people want to know what they are letting themselves in for. Zurich’s electorate voted in favour of the proposal in 2012, enabling the vision to become a reality.

Heimplatz takes centre stage

With the extension now complete, the Kunsthaus is more engaged than ever in dialogue with leading international museums. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the dimensions of Chipperfield’s new building rival those of the historically developed museum complex on the other side of the square.

As you walk from the university to the Kunsthaus, the extension is simply impossible to overlook. But the change of scale is necessary, because the value now accorded to art necessitates a fittingly grand setting for it. The completion of the construction project is a good opportunity to look back at the development of the Kunsthaus.

A long history

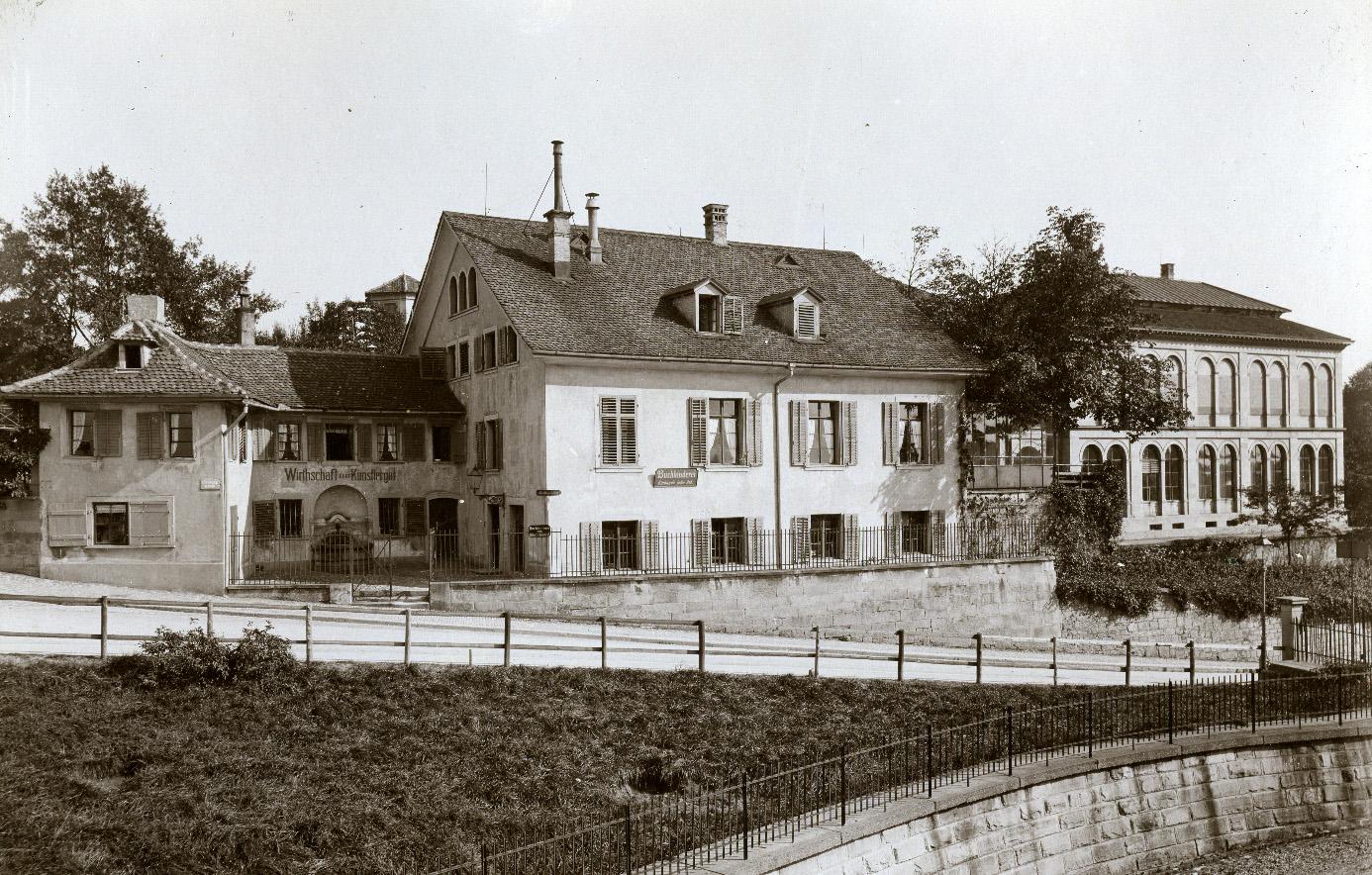

In comparison with its current grandeur, the beginnings of the Kunsthaus are modest. The story starts in 1813, when the Zürcher Künstlergesellschaft acquires a plot of land close to what is now the university. The first exhibition building is constructed on the “Künstlergütli” in 1847. Some years later, Zurich’s cultural facilities extend to a further location: the Künstlerhaus, which opens in 1895 on Talstrasse opposite the stock exchange.

Behind the two constructions are a pair of associations that merge in 1896 to form the Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft, the patron association of today’s Kunsthaus. The occasional coexistence of two institutions is nothing unusual; elsewhere, the young generation of artists comes together in “secessions”, such as the one in Vienna. So Zurich is in fact catching up with the latest developments – a sign that the city is evolving both economically and culturally.

Zurich makes a statement

The urban transformation of Zurich that this entails spells the end for the two preceding buildings. In their place comes Karl Moser’s Kunsthaus on Heimplatz. The city supplies the land and pays part of the construction costs, a recognition that a museum of this kind is an essential part of the cityscape. The building is inaugurated in 1910.

The architecture features a stylistic transition that suggests reform rather than revolution. Moser employs traditional design elements, but he has simplified them, while the differing appearance of the tall main building and the flat exhibition wing underscores, rather than downplays, their distinct functions.

It is not until later that Moser makes the final switch to modernism, with clear lines and a move away from echoes of historical building forms. This can be seen in his plans for annexes to the Kunsthaus; though only a small extension to the rear is actually built, in 1925.

A new venue for exhibitions

The next stage, first mooted during the Second World War, is not completed until 1956. This time the architects are Hans and Kurt Pfister. The projecting Pfister building, situated opposite the old exhibition wing, dominates the vista of Heimplatz to this day.

The wing stands apart from the existing Kunsthaus in two ways. The first is its intended purpose: to create a spacious venue for temporary exhibitions. The second is that it is funded by a dominant and not uncontroversial personality: Emil Georg Bührle. His money stands at the beginning of a lengthy planning history. Its outcome sets new standards: it is executed in concrete and glass and employs state-of-the-art technology – the hallmarks of a progressive post-war mentality, with a formal language that is now very much back in fashion.

Growth on many levels

The third extension designed by Erwin Müller and built between 1970 and 1976 is a very different proposition. It too was financed by a generous gift, but its outward appearance is less prestigious. It could be argued that even the choice of location, to the rear of the Kunsthaus on Hirschengraben, is symptomatic of an age which frowns upon unbridled growth. Yet quite simply, the site is the only option for enlarging the Kunsthaus.

The Müller wing is sometimes viewed as a well-intentioned piece of architecture that strives to fulfil its allotted function without drawing attention to itself. Yet that perception is unfair: planned from the inside out, the multifaceted suite of rooms has much in common with, for example, the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, which was completed at the same time. It employs a complex layering of levels and a striking system of lighting. The architecture here is far from a reserved “white cube”.

A new era?

Sir David Chipperfield’s extension forms an architectural counterpoint to the old building on the other side of Heimplatz, and is now ready for the art to move in. The concentration on a narrow range of construction materials, with brass ingeniously employed to eye-catching effect, means that the building exudes calm, both outside and in. The route axis leading through the connecting tunnel into the hall and on to the art garden at the back is a well-thought-out attempt to link old and new.

It is already clear that, from an urban planning perspective, the design as executed was the right choice. Despite numerous constraints, Zurich now has a new, attractive venue that is not a temple to culture but a house for art and people.

The Kunsthaus at the ZB

The Zentralbibliothek Zürich holds a wealth of information on the history of the institution, the collection and the buildings. Examples include:

- a monograph on the Moser building

- documentation on the extension by the Pfister brothers

- a research report on the role of Emil Bührle

- the commemorative publication marking the completion of the Müller building

- the competition report for the current new construction project

- the latest publications from the Kunsthaus

A further project that links the ZB Zürich to the Kunsthaus is the digitisation of the old exhibition catalogues. Our Digitisation Centre has prepared some 700 catalogues published between 1801 and 1949 for presentation online.

Dr. Lothar Schmitt, art, architecture and archaeology expert

August 2021

Header image: Posters outside the entrance to the extension (image: Lothar Schmitt)