Zurich’s economy – highlights

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Zurich becomes a motor of the Swiss economy. The city’s industry, railway construction and banking sector help to usher in the modern era. Come with us on a tour of Zurich’s economic history, from industrialisation to the Swissair grounding.

From plough to factory chimney

Industrialisation is a social and economic transformation that brings sweeping changes to the canton of Zurich. Rural families who work from home weaving and spinning by hand for the textile industry, particularly in the Zürcher Oberland, will soon be working in factories. The first mechanical looms come to Switzerland from England in the 1830s.

Entrepreneurs build their factories where there is water to power water wheels, and later turbines. This exceptional development changes the face of the countryside, villages and towns. Most prominent today are the above-ground constructions from that era: factories, factory-owners’ houses and waterworks. A walk along the Zürcher Oberland industry trail reveals numerous vestiges of that pioneering economic age.

Machine builders

Architect Hans Caspar Escher and banker Salomon von Wyss establish a cotton mill at Zurich’s Neumühle in 1805. The duo use the latest weaving machines from England, continually improving them in their own machinery shop.

Their technically minded entrepreneurship lays the foundations for an important company: soon, Escher, Wyss & Cie. is the leading machine builder in the canton of Zurich, and in the 20th century it becomes a global business.

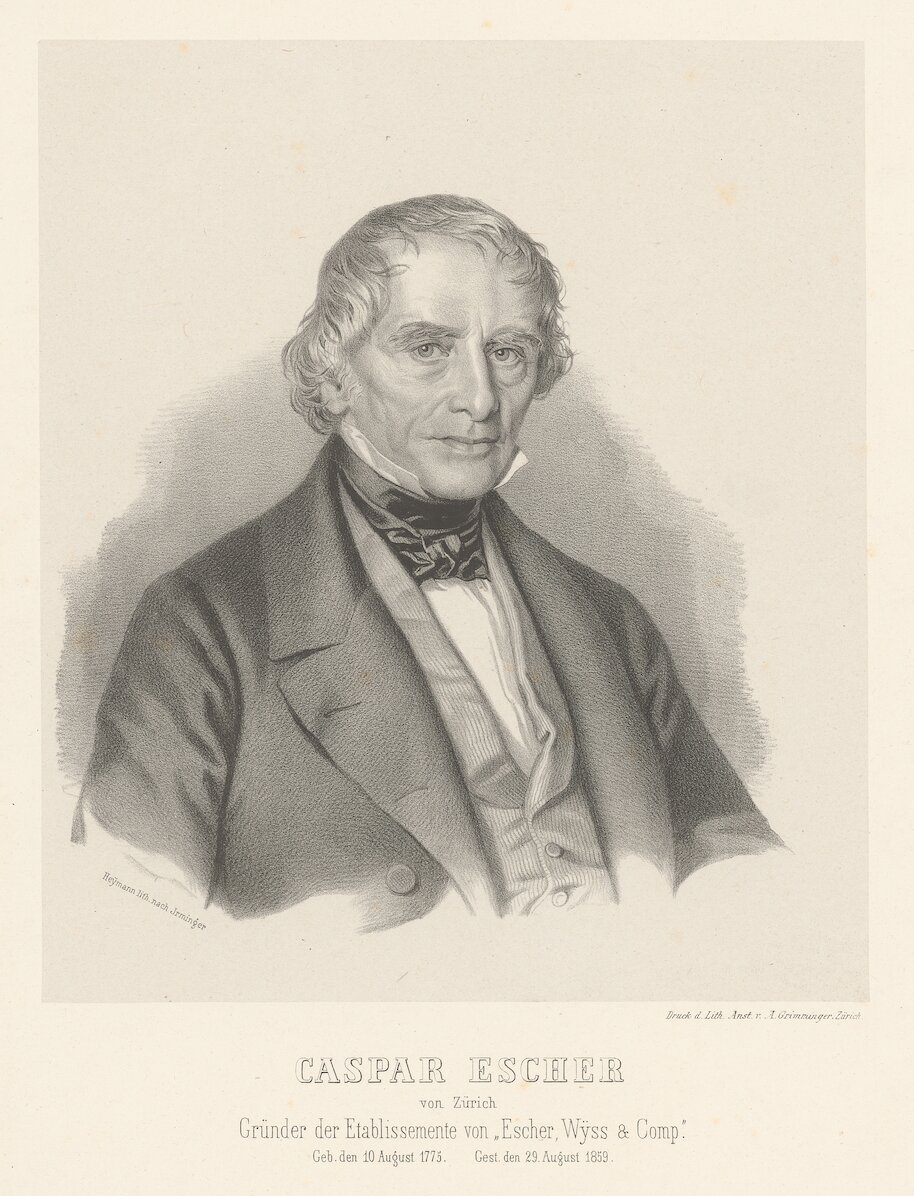

Caspar Escher (1775–1859), the co-founder of Escher, Wyss & Cie.

Caspar Escher (1775–1859), the co-founder of Escher, Wyss & Cie.

Honegger looms

The Honegger family are farmers in Rüti. As a second business they have two spinning machines driven by water power. The spinning mill in Rüti becomes a factory, and the family’s son Caspar Honegger a successful businessman.

He builds a second factory in Siebnen with mechanical looms from England. Later he sets up his own workshop where he manufactures his own looms, which he names after himself. Thus a textile maker becomes a machine builder.

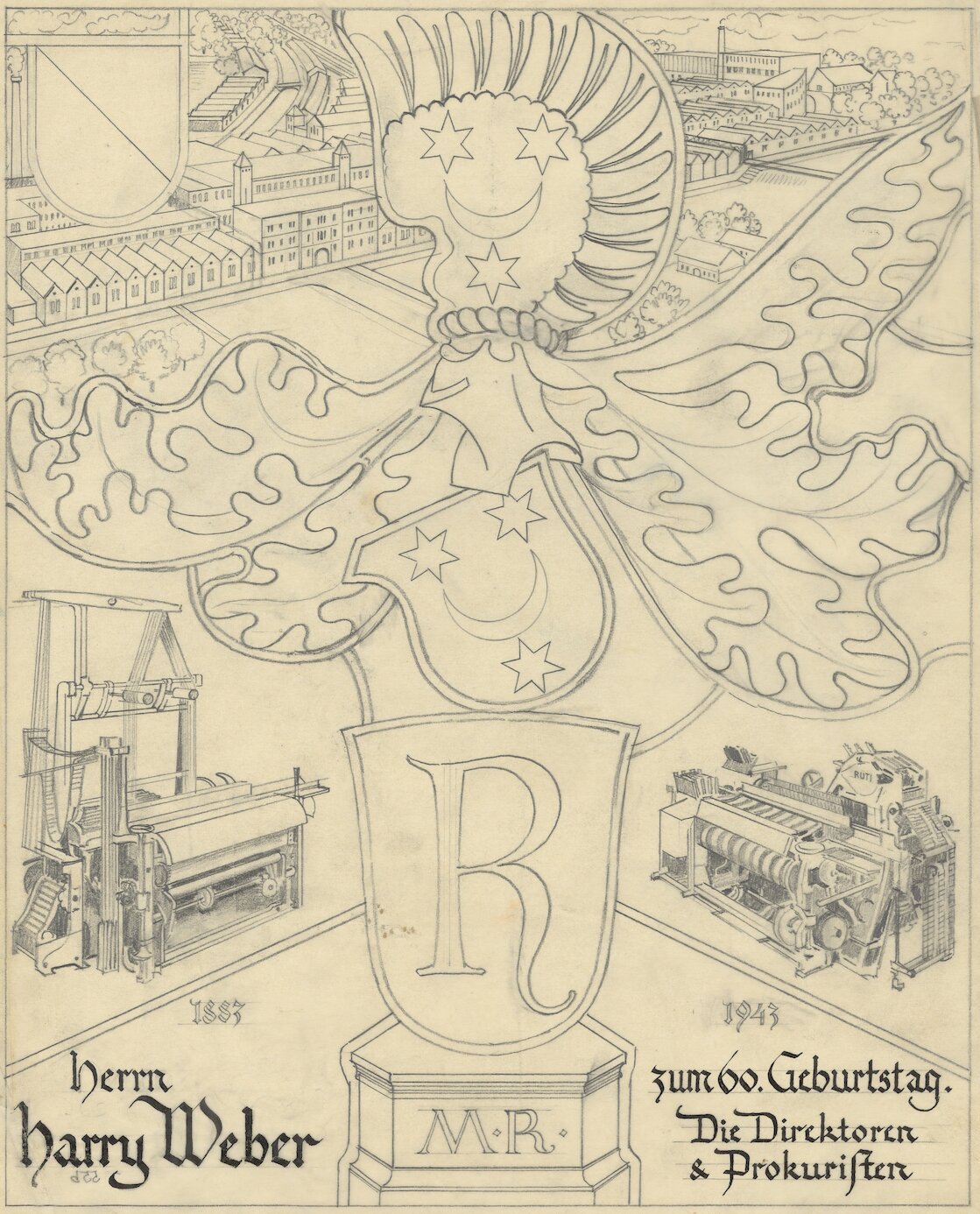

To the left of the picture a Honegger loom, at top the factory site in Rüti

To the left of the picture a Honegger loom, at top the factory site in Rüti

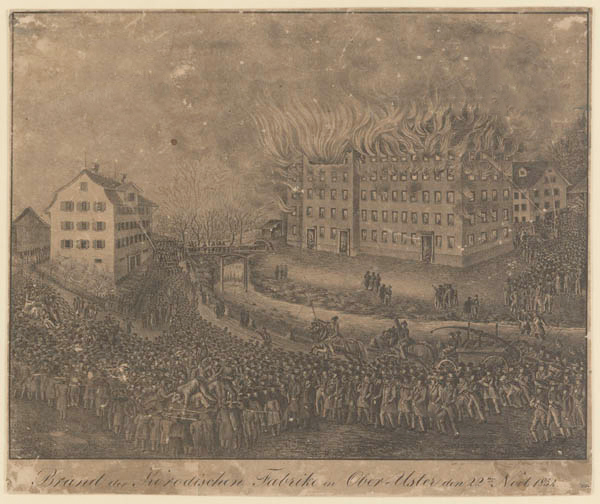

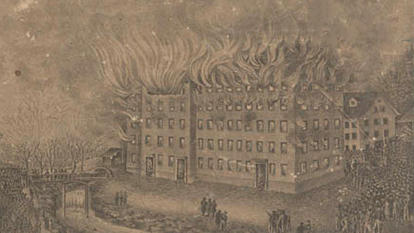

The great fire of Uster

On 22 November 1832 the Corrodi & Pfister spinning and weaving mill in Uster goes up in flames. What has happened? Zurich’s rural areas are disadvantaged compared with the city. In a memorandum known as the “Uster Memorial”, the rural population calls for constitutional reform and the removal of the weaving machines from Corrodi & Pfister. But the machines remain in place, and after two years the home weavers and small manufacturers from the Zürcher Oberland have had enough. They destroy the factory. The Uster fire is the most significant act of machinery destruction in Switzerland.

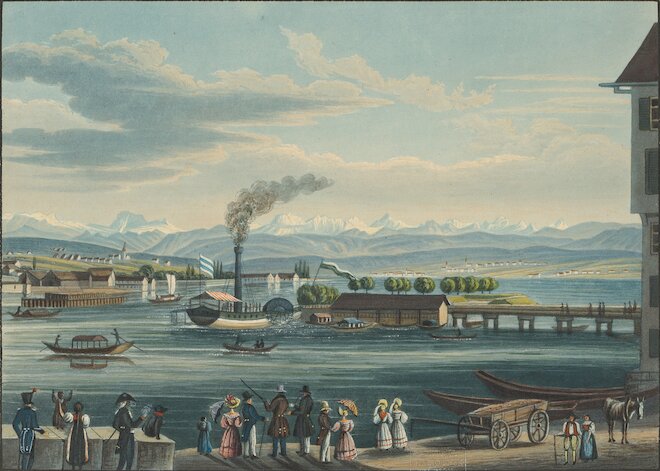

The first paddle steamer on Lake Zurich

The boom in industry and commerce goes hand in hand with a modernisation of Zurich’s transport system. The “Minerva”, Zurich’s first paddle steamer, embarks on its maiden voyage on Lake Zurich on 19 July 1835, to the sound of cannon fire and pealing bells. At the time, there are no landing stages. Passengers are conveyed to the steamer in a small boat, since the larger vessel often has to moor far out on the lake.

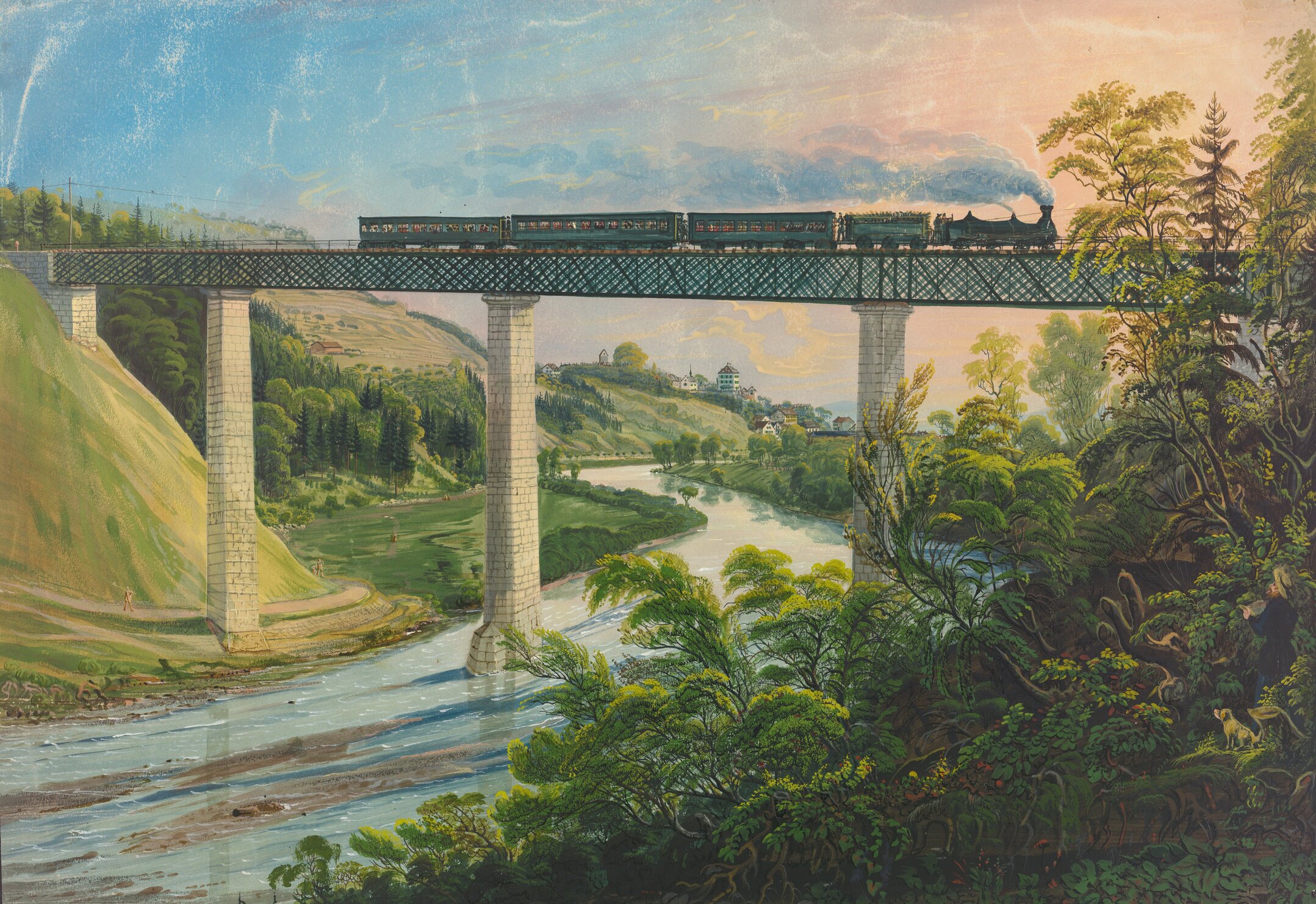

The railways come to Switzerland

“Steam is creating a new world, and all peoples are rushing to find their place in the new division of the Earth and set themselves up there”, writes the NZZ in 1852.

Steam-powered machines and steam locomotives play a major role in the second phase of industrialisation. Switzerland, however, is a latecomer in terms of railway construction. The first tracks on Swiss soil are not laid until 1844 in Basel, and extending the line into the Central Plateau proves a difficult undertaking. By that time, thousands of kilometres of railway lines have already been constructed in Germany, France and Austria.

Steam, smoke and Spanischbrötli

The Swiss Northern Railway plans to build a line from Zurich to Basel. But the absence of appropriate legislation holds the project back, and initially the Northern Railway only runs between Zurich and Baden.

The journey between the two towns takes three quarters of an hour – far quicker than the two to three hours for the mail coach. Upper-crust Zurich households can now have their Spanischbrötli , a speciality pastry from Baden, delivered conveniently to them at home. Soon, the Northern Railway is being popularly referred to as the Spanischbrötli Railway.

Money for the railway

The Zurich politician and railway pioneer Alfred Escher needs money for his rail projects – lots of it. Rather than relying on foreign financial backers, Escher, along with other like-minded individuals from politics and the textile industry, founds the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt (SKA). It soon becomes the leading commercial bank in Switzerland, and is very important for the funding of rail construction. The founding of SKA is a milestone for Zurich’s financial centre.

Alfred Escher (1819–1882), a leading economic policymaker in Zurich

Alfred Escher (1819–1882), a leading economic policymaker in Zurich

National Exhibition in Zurich

The first Swiss National Exhibition takes place in Zurich in 1883 at Platzspitz. It is a major event of countrywide importance, attracting 5,000 exhibitors and 1.7 million visitors.

Its focus is on the nation’s economic and industrial competitiveness and faith in progress. Of particular interest is the industry exhibition, which displays the latest products of contemporary engineering. Ausstellungsstrasse (“Exhibition Road”) in Zurich harks back to this event.

Entrance to the machine hall at the National Exhibition of 1883

Entrance to the machine hall at the National Exhibition of 1883

Belle époque and the cannons’ roar

During the belle époque, everything becomes bigger and more glamorous. The bourgeoisie, with its faith in progress underpinned by science and technology, is in a strong position during the two decades leading up to 1914, but the working class too benefits from the general economic growth.

Then the upturn comes to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the First World War. Nevertheless, the new institutions and developments in the early years of the 20th century continue to shape life in Switzerland today: nationalisation of the railways, countrywide business censuses and the Swiss National Bank. The interwar period brings a brief economic upswing, while the end of the 20th century witnesses the global economic crisis.

Propellers and jets

At the start of the 20th century, Switzerland becomes home to aviation pioneers. Experts agree that a site near Dübendorf is particularly suitable for an airfield, and by 1910 the Swiss Aerodrome Society has opened Dübendorf aerodrome.

As Switzerland’s first military airfield, sometime hub of European civil aviation, venue for airshows and the launch base for Auguste Piccard’s flight into the stratosphere, Dübendorf has often found itself in the headlines. Today it is regarded as the cradle of Swiss aviation.

Renée Schwarzenbach flies her Ju F 13 from Dübendorf aerodrome to Munich

Renée Schwarzenbach flies her Ju F 13 from Dübendorf aerodrome to Munich

National strike

From 12 to 14 November 1918 Switzerland’s working population downs tools. The national strike enters the history books as the gravest political and social crisis faced by the Federal State.

The strike is preceded by food rationing, impoverishment of the working class and other repercussions of the First World War. The outbreak of Spanish flu further exacerbates an already dire situation.

The events are also reflected in works of literature such as Kurt Guggenheim’s Zurich novel “Alles in Allem”.

Metal, machines and wrecking balls

The First World War gives a further boost to the flourishing metal processing industry. Zurich is a booming metropolis, thanks to the efficient interplay of entrepreneurship and banking. In 1937 the social partners sign the Peace Agreement in the Swiss Metal and Machine Industry, which is designed to ensure workplace harmony in the then strike-ridden sector and remains influential today.

The boom of the 1950s to 1970s is followed by decline. Production facilities that are no longer needed, such as the Sulzer plant in Winterthur, are put to new use or demolished.

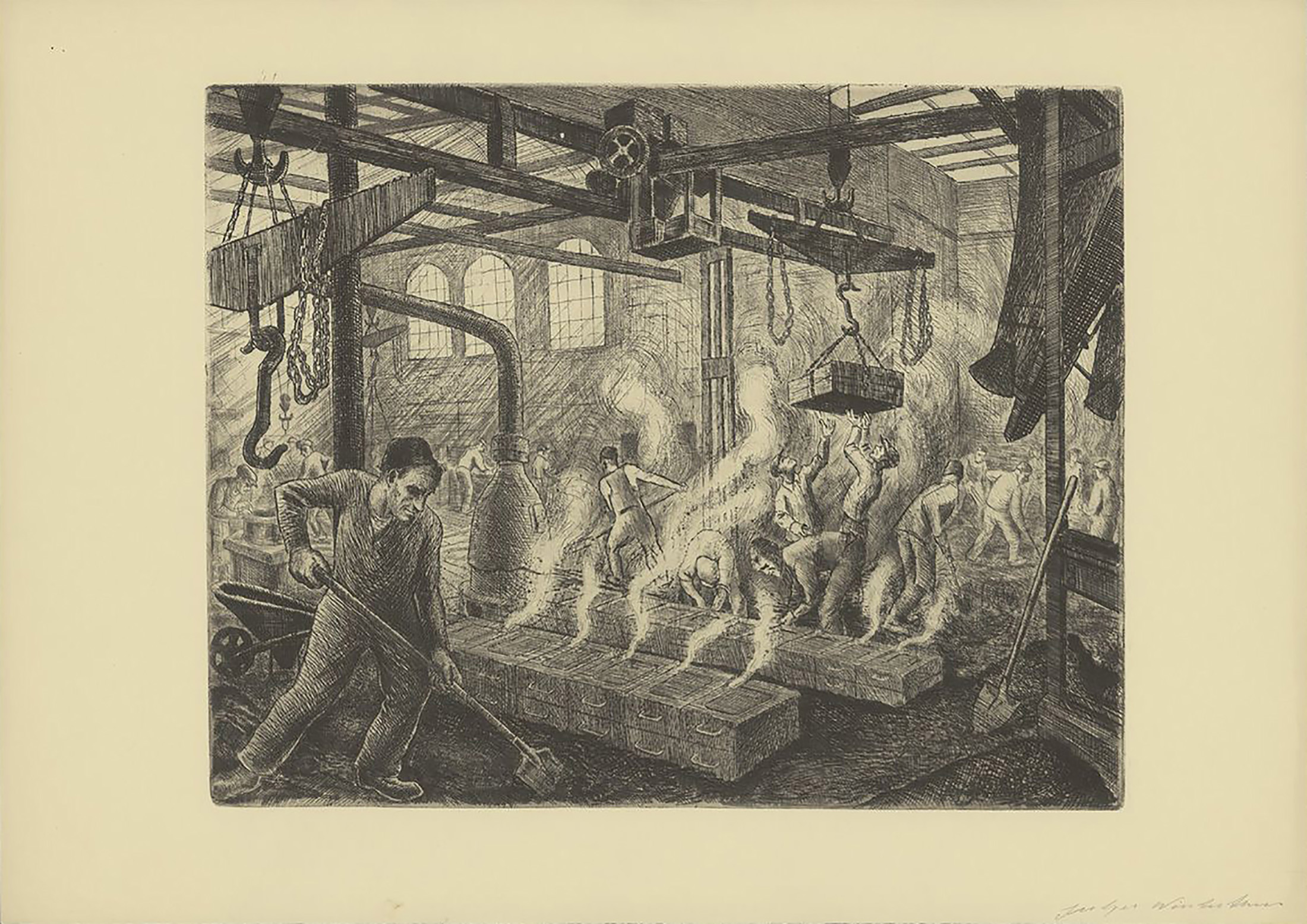

Probably the foundry at the Sulzer plant in Winterthur. The company initially produces boilers and steam engines, then later turbines and pumps.

Probably the foundry at the Sulzer plant in Winterthur. The company initially produces boilers and steam engines, then later turbines and pumps.

Boom after the Second World War

The post-war period is a time of unprecedented economic growth that endures into the 1970s. Extensive construction activity and growing mobility change the face of Zurich and Switzerland.

The country moves from a war economy to a social market economy. The years that follow witness a boom: hydroelectric power generation is expanded, new roads and the first motorways are built, and Switzerland consolidates its welfare state with the introduction of old age and survivor’s insurance and disability insurance. From the 1960s onwards, economic growth fuels demand for foreign labour in the construction and tourism industries. The oil crisis of the 1970s, however, brings the economic upswing to an abrupt end.

Money, gold and myth

During the two global conflicts, Zurich’s banking and financial centre joins the top rank. After 1945, what the Economist magazine refers to years later as the “golden age of Swiss banking” begins. Switzerland’s role during the war years, the bank-client confidentiality introduced in the 1930s, Swiss tax policy and the strong Swiss franc make Zurich one of the leading hubs of international capital. The epicentre of Zurich’s banking industry is Paradeplatz.

Oil sheikhs and bicycles

The oil crisis deals a huge blow to the global economy, as agreements between oil-exporting countries lead to a huge rise in the prices of oil products. The Swiss Federal Council orders three car-free Sundays, when no motor vehicles can be driven anywhere in the country. Roads are transformed into cycle paths, even in Zurich.

An icon comes down to Earth

On 2 October 2001, the national airline Swissair ceases operations owing to lack of liquidity. Passengers and pilots are left stranded around the world, including at Zurich Airport in Kloten. The “grounding” is arguably the most spectacular bankruptcy of the post-war era and an event that profoundly affects the Swiss public.

It is preceded by a gradual decline that begins back in the late 1980s. Swissair is unable to compete in the liberalised aviation sector.

Further reading

Our economics experts recommend:

- Joseph Jung: “Das Laboratorium des Fortschritts: Die Schweiz Im 19. Jahrhundert”

Jung examines how the small state of Switzerland becomes an economic powerhouse. An entertaining guide to economic history. - Patrick Halbeisen et al.: “Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Schweiz im 20. Jahrhundert”

An extensive, academic analysis of individual sectors based on statistical estimates of the economic trends in Switzerland. - Jean-François Bergier: “Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Schweiz: Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart”

A comprehensive overview of Swiss economic history up to the 1980s by a seasoned expert in the field. Still worth reading.

The Turicensia Department recommends books, articles, videos and more on this topic from the Zurich Bibliography. For more fascinating insights into the textile industry see the Schwarzenbach family and company archive in the Manuscript Department.