Zurich by Wick

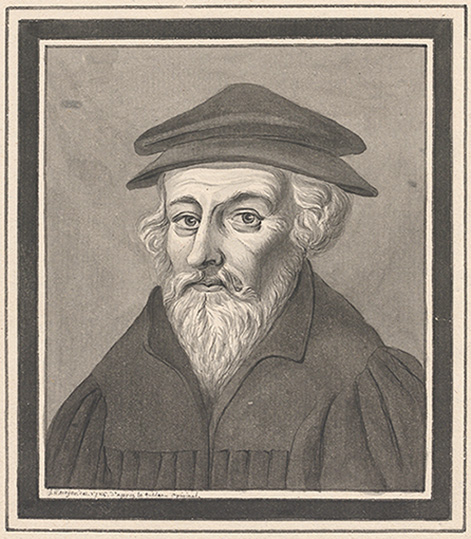

Zurich-based canon Johann Jakob Wick (1522–1588) spent almost 30 years collecting and recording news from his hometown and around the world. Known as Wickiana, these documents are among the most popular historical sources at Zentralbibliothek Zürich. Join us on our whistle-stop tour through them.

A collector of news

‘Mr Hanns Jacob Wick, a happy, well-educated and cooperative man.’

From the letter of recommendation for Wick’s appointment as second archdeacon at Grossmünster church, 1557.

Johann Jakob Wick was a child of the Reformation through and through: the spread of Protestantism was already underway when he was born in Zurich in 1522. A city boy, he attended Latin school at the former Kappel monastery, where Heinrich Bullinger taught, and at Fraumünster church. He studied theology in Tübingen, Marburg and Leipzig before being given his first parish, Witikon, in 1542 at the age of 20. In 1552, he came to Zurich’s Spital zu Predigern (where the Zentralbibliothek is now located) as a priest, an assignment which plunged him into the midst of human suffering.

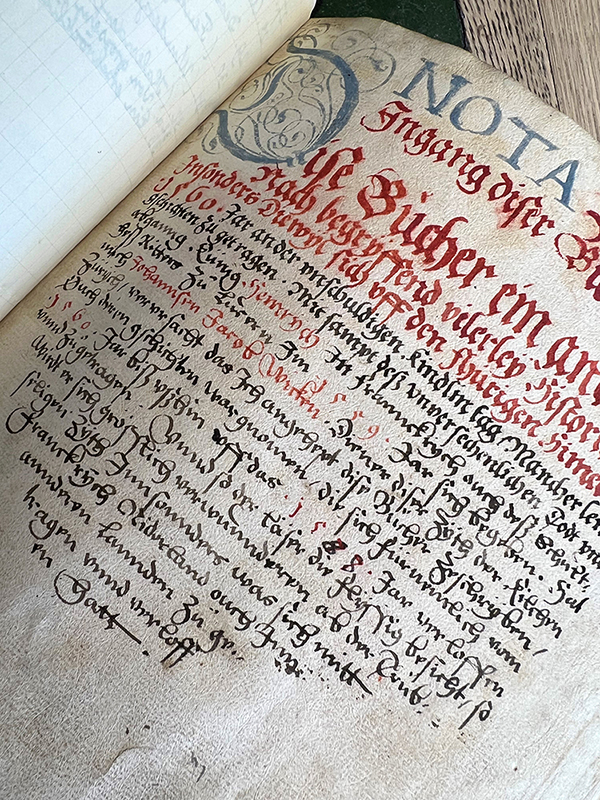

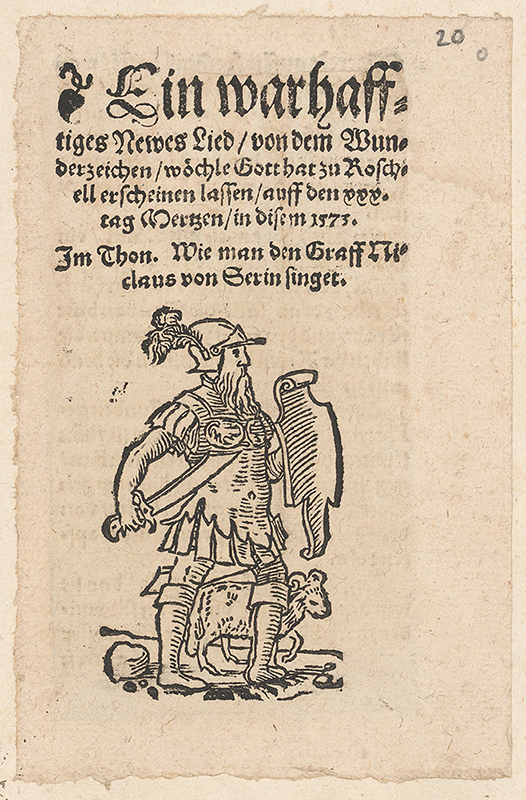

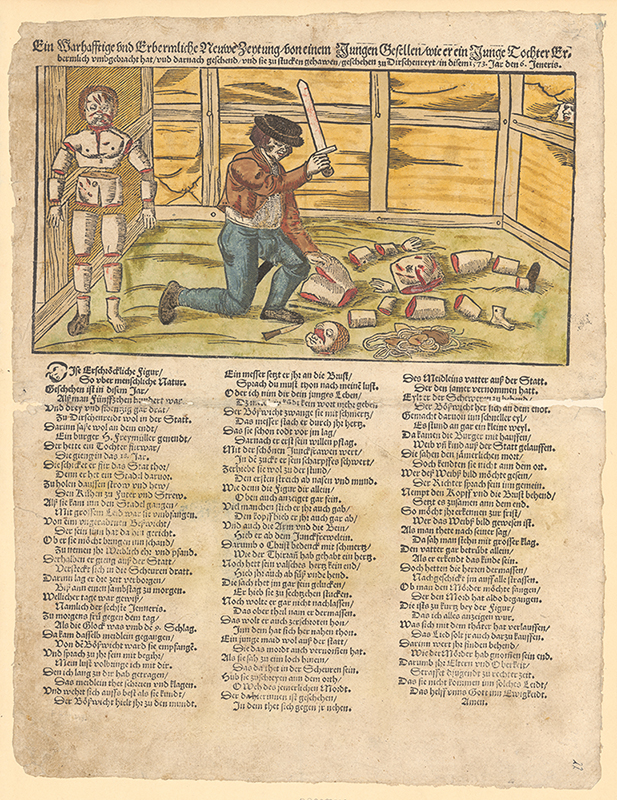

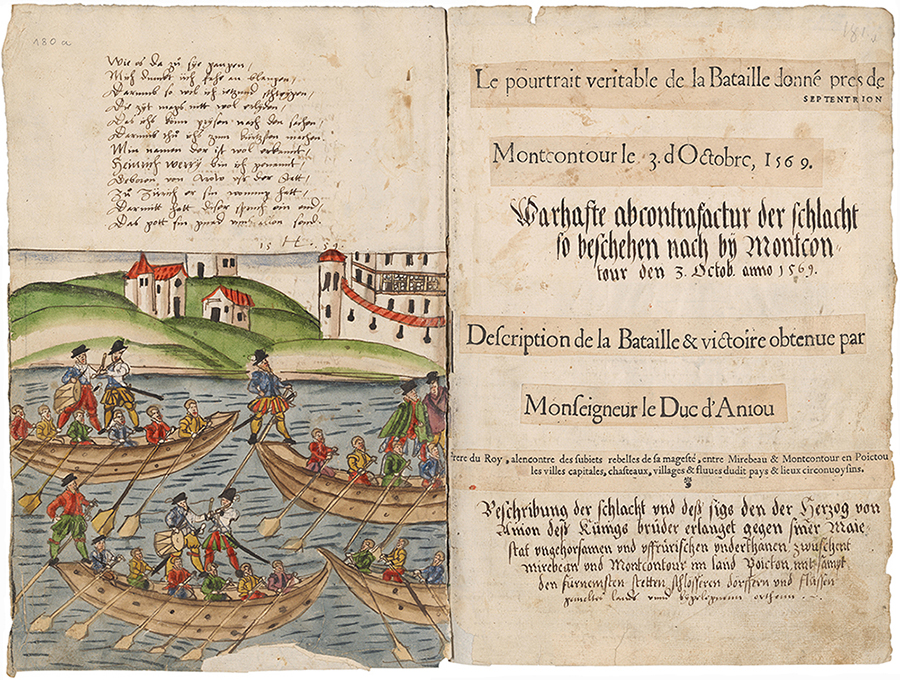

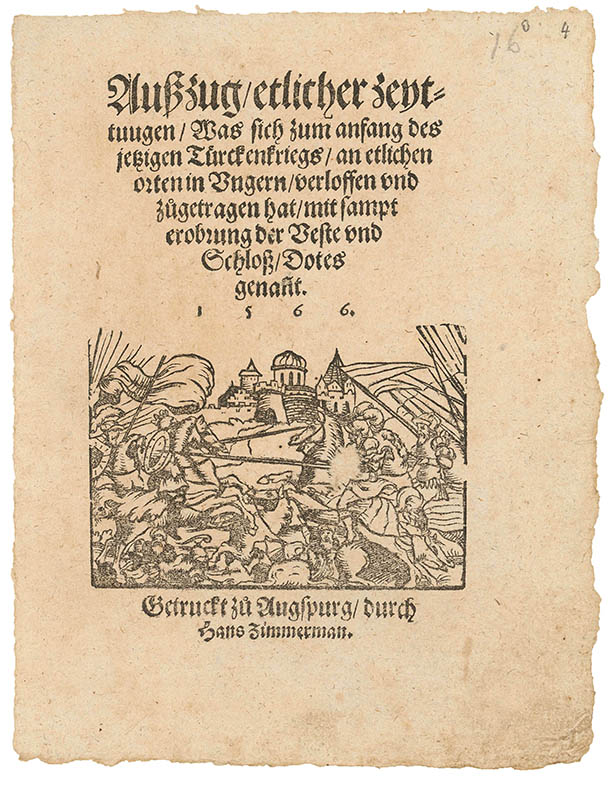

As second archdeacon and canon at Grossmünster abbey, he started to record contemporary news in 1560. He added drawings, printed pamphlets, handbills (known as ‘new gazettes’, or ‘Neuwe Zeytunge’ in German) and letters, filling 24 volumes comprising around 13,000 pages by his death in 1588.

…and his informants

People love liking and sharing news updates – but this isn’t a modern phenomenon. Canon Wick was also able to rely on a network and lots of different channels: people knocked on his door when they had something interesting to share.

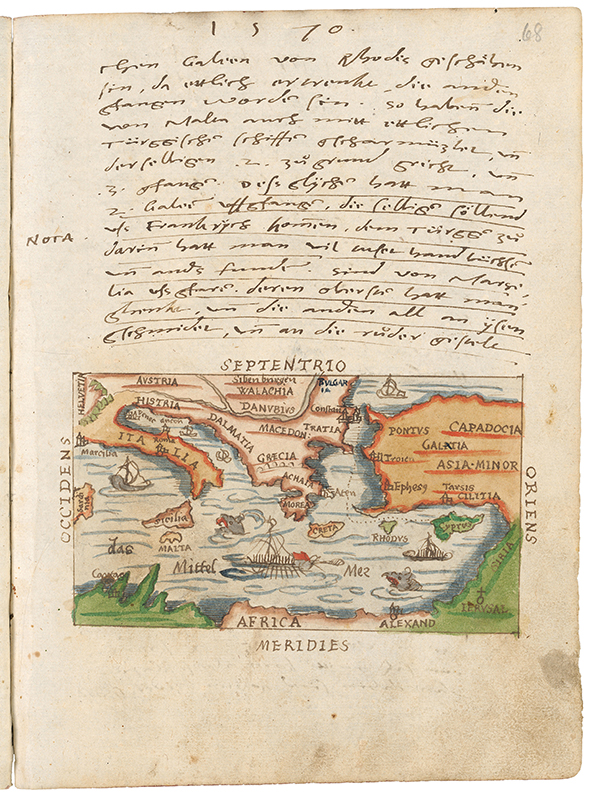

His most important informant was Zurich-based reformer Heinrich Bullinger, who engaged in copious correspondence with acquaintances in Italy, England and Eastern Europe. Other canons, the Zurich-based doctor and nature researcher Konrad Gessner, the publisher Christoph Froschauer and the Electoral Palatinate politician Count Ludwig von Wittgenstein also numbered among Wick’s sources. Fellow Protestant priests supplied him with information on goings-on in their villages.

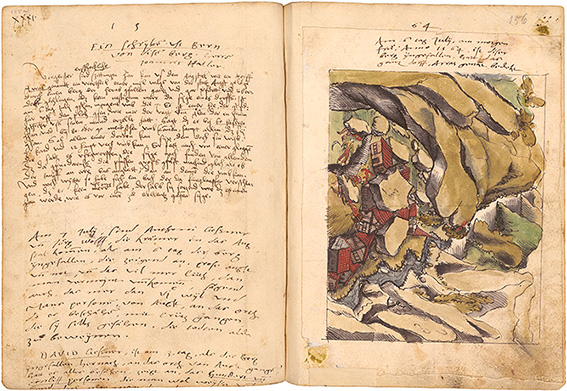

Witnesses were often mentioned by name to enhance credibility. For instance, the priest Johannes Haller, who sent a letter reporting on a landslide, made reference to two eye-witnesses and a reporter who attended the site of the accident three days later. Hearsay also counted as source: ‘There is someone here who has been in that place ever since, as the governor (Vogt) of Aigle, who sent him there, explained to me. He said...’

We only know the identities of some of the artists and amateurs who contributed the 1,028 pen drawings.

A multimedia record of the era

‘I have also recognised the care with which you have collected and written down these notable things and events in these books; it would be very useful for anyone to be able to recall them.’

Councillor Johann Rudolf Wellenberg to Johann Jakob Wick, 1574.

Johann Jakob Wick’s chronicles were highly regarded even during his lifetime. As a result, a council resolution saw them be placed in the care of the abbey library of Zurich’s Grossmünster after his death. After this institution was dissolved, the collection was acquired by Zurich city library in 1835. One volume passed into private hands and was temporarily lost, but made its way back to the others in the twentieth century. The large-format broadsheets have been stored separately since 1925 for conservation reasons.

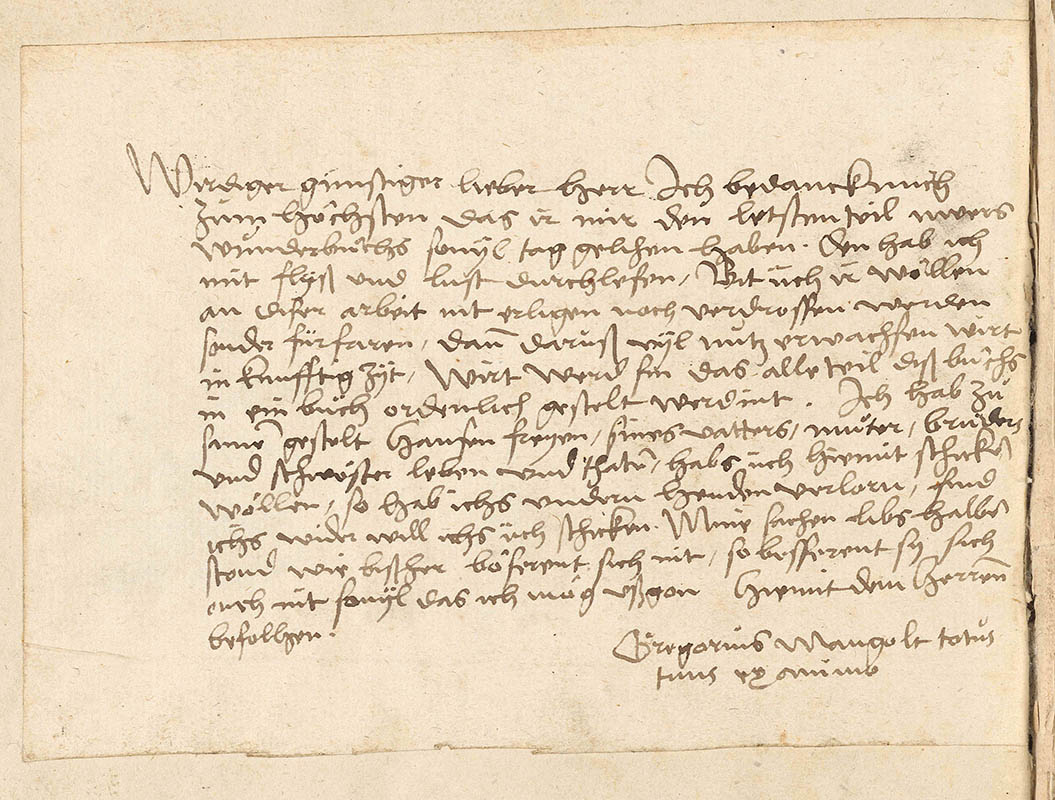

‘I beseech you, do not cease or slow down this work: instead, continue with it, as it will be of great utility in the future.’

German chronicler Gregor Mangolt to Johann Jakob Wick, 1570.

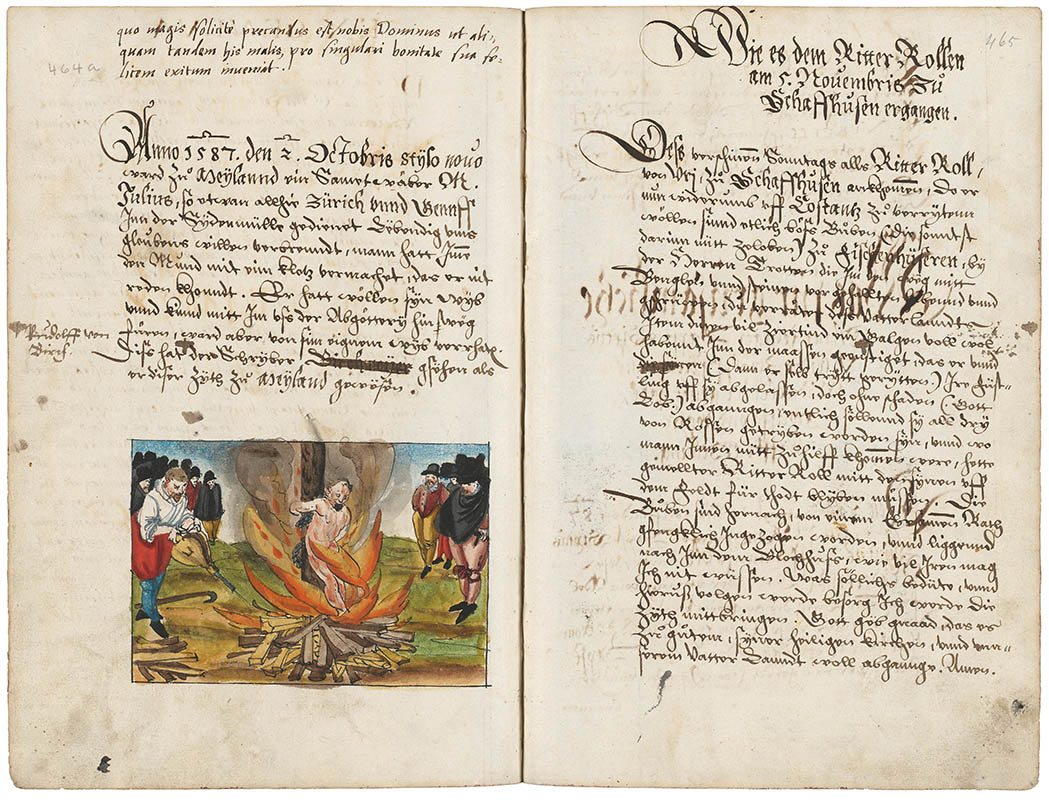

Wick’s collection of news has lost none of its appeal in the twenty-first century. It is among the most popular sources at ZB Zürich – not least due to its explicit illustrations of witch-burnings and torture scenes. However, the Wickiana are much more diverse and multi-faceted than this. They combine originals and copies, news, notes, letters, prints, drawings and maps to create a multimedia record of the era, as illustrated by the following gallery of images.

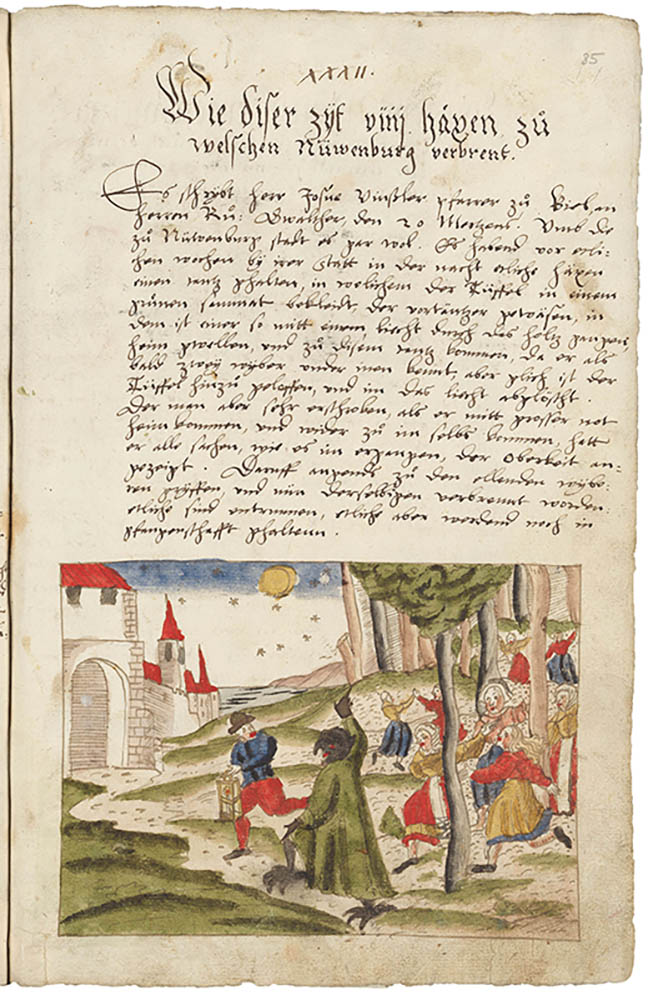

Portents – a sign from God

Alongside news on religious tensions and conflicts – including anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish pamphlets – reference is frequently made to portents. These are natural events and miracles seen as a sign from God, be they monstrous beings and deformities, unusual celestial phenomena, weather-related disasters or epidemics. The task at hand was to identify and classify these signs. Wick also documented their consequences: famine, price increases, deaths. He sometimes recorded what they meant, but he more often gave up:

‘The Lord God alone knows what He means by this: He wants everything to change for the better.’

Comment by Johann Jakob Wick in the first volume of his Wickiana.

Wick was neither a reporter nor an ethnologist: he collected what was given to him and was restrained in his comments. As a result, the Wickiana are not an easy read, due to their sheer volume. This was also recognised by the authorities in Zurich, who kept the volumes under lock and key in Grossmünster abbey from 1588 onwards.

Chronicles of a ‘turbulent time’

All told, this paints a picture of a ‘turbulent time’, as Wick notes on the title page of his first volume. The Day of Judgement and, by extension, the end of the contemporary epoch were surely on the horizon. The appropriate response to this diagnosis of the era was collective repentance, the eschewal of sinful ways of living and a reformation of faith.

The canon’s deeply subjective collection was, therefore, also grounded in pastoral concerns: he wished to expose rampant evil and show God’s intervention. Words like superstition, sensationalism or sadism do not do justice to this.

Wick’s record of Zurich

Johann Jakob Wick gathered remarkable pieces of news from Europe, Russia and the Ottoman Empire – some credible, others more dubious. His collection is primarily composed of reports from Switzerland, the Holy Roman Empire and France. In our timeline, we take a closer look at ten events in Zurich that occupied Wick and those around him.

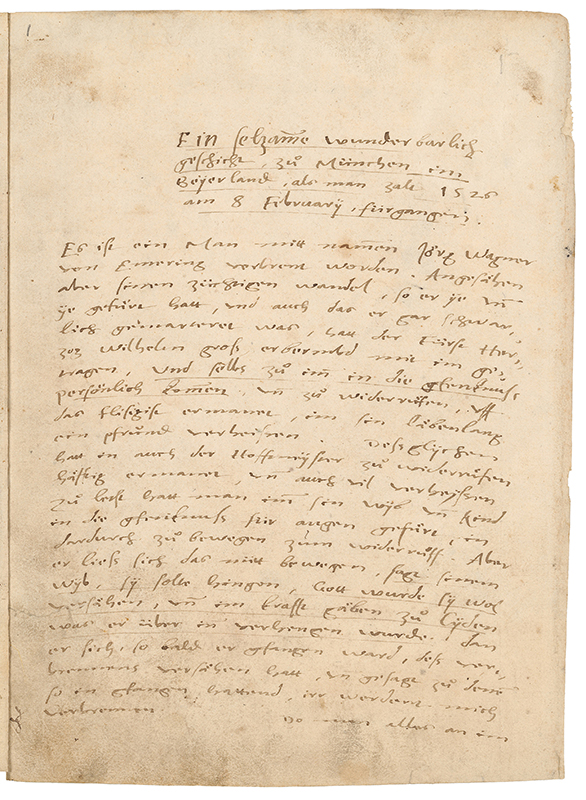

An infamous Zurich witch

On 2 March 1546, the Reformer Heinrich Bullinger wrote to Basel clergyman Oswald Myconius to inform him that Agatha Studler, a ‘notorious Circe’ (witch), had been sentenced to death. As she prayed for mercy, she was drowned instead of burnt. The illustration shows how she was thrown in the River Limmat.

From today’s perspective, it appears likely that the wealthy city-dwelling divorcée’s permissive and extravagant lifestyle was the cause of her undoing. Following accusations from a baker and his wife, she was thrown in the Wellenberg prison tower and tortured until she ‘confessed’ to poisoning and cursing other people. Such smears, judgements and incidents of torture are a bleak and unfortunate chapter in Zurich’s history.

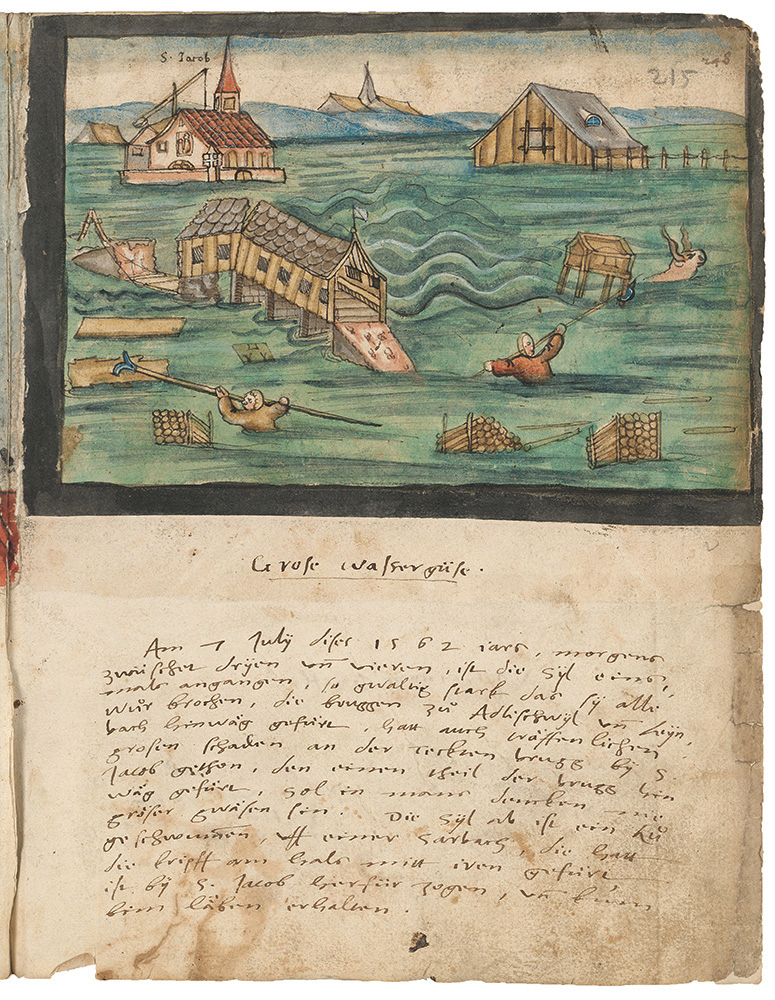

Everything is in the river

God’s warning signs included natural disasters such as landslides and floods. The river Sihl burst its banks early in the morning on 7 July 1562. Every dam broke, and the Adliswil and Leimbach bridges were carried away by the waters. The covered bridge at St. Jakob was damaged, and part of it, too, was swept away.

In the whole-page illustration, the little church of St. Jakob pokes out of the waters, where the wooden bridge and cattle are seen to drift alongside people fishing for their belongings. The anonymous illustrator drew on a detail from the story on the image’s far right: ‘A cow came swimming down the Sihl on a black poplar tree, bringing its feed trough with it.’ The cow was safely pulled from the water.

A procession collapses

The weight of the annual parish fair procession was too great, and on 11 September 1566, the Obere Brücke bridge by the Wasserkirche (later the Helmhausbrücke/Münsterbrücke) collapsed. Eight people drowned, including five children. The bridge’s collapse wasn’t unprecedented: back in 1375, the wooden Untere Brücke bridge had collapsed during a church procession on 4 June. However, according to the Reformed writer, the recurrence of tragedy did not move the authorities to call off the ‘papist’ religious ceremony.

The commentary is brief, but the illustration has been created with plenty of imagination and attention to detail. The mighty scoop wheel and the well can be seen, while in the background, the image depicts the Wellenberg prison tower and wooden palisades facing the lake.

In 1581, Wick recorded another Zurich bridge accident.

Lots of broken pottery

On 16 June 1570, a horse owned by Jakob Kuster spooked underneath the arcade at the Zunfthaus zur Zimmerleuten and demolished a potter’s stall with its cart. The victim of the damage immediately demanded 30 guilders. The men called in to settle the dispute, Governor (Statthalter) Wegmann and Bailiff Ziegler, did not respond to his claim for damages, and granted only a little more than half of what he asked.

This story of an incident in everyday city life, whose moral we may struggle to discern today, captured the collector and illustrator’s imagination. Behind the scene of the accident, with all the broken pottery and agitated people, he also depicted the cause of the commotion: the Limmat at high water had scared the horse.

The Wickiana collection records other accidents befalling humans and animals.

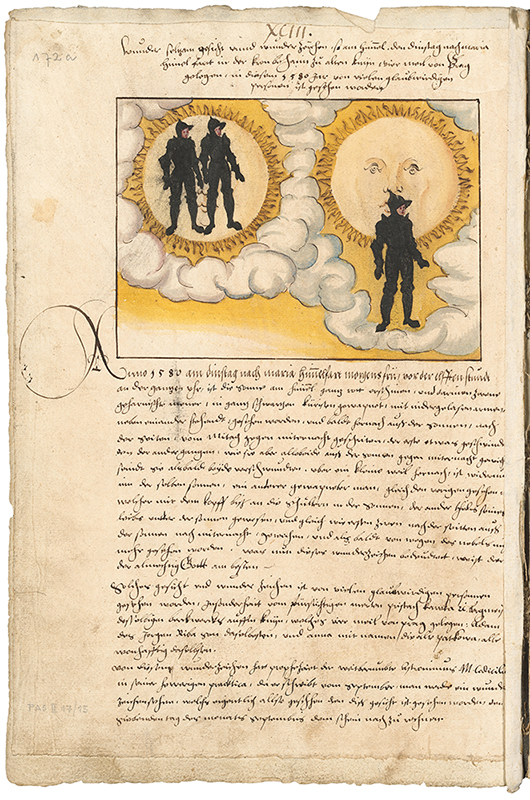

Zurich sees red

On 29 September 1571, Michaelmas, the people of Zurich were confused by the sun. In the morning, it shone golden yellow, and at noon it flooded blood-red into every building, as if red panels had been placed on the windows. In the evening, it turned white like the moon and seemed to go out. A worried Wick listed several previous disastrous events preceded by the same sign.

The illustrator gave the red planet two eyes, a big, bulbous nose, and full lips. On the banks of the Limmat opposite the Fraumünster cathedral, four gesticulating citizens discuss the spectacle. Pointing figures like this were also popular in printed pamphlets. Wick gathered reports of other celestial events.

Struck by lightning

On 5 May 1572, lightning struck the Zurich Grossmünster’s tower and set it on fire. While the damage took just a day to repair, the fact that the Grossmünster – ‘the epicentre of the Zurich Reformation’ according to Luca Beeler – had been hit by lightning could not be written off as a mere freak weather event. This was also suspected to be a warning or punishment from God, as an ominous blood-red sun was said to have appeared in the skies over Zurich at the time.

Peopled with many characters, the illustration recalls the style known as outsider art or art brut, which challenges prevailing artistic conventions with storytelling, expression and subjectivity.

Wick recorded many lightning strikes and their sometimes harrowing consequences, interpreting them as evidence of God’s might.

Fatal heartbreak

On 12 April 1579, the lovelorn emissary of Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria threw himself out of a window of the Zum Schwert inn into the Limmat and to his death. Wick vividly depicted this Zurich romantic tragedy, believing it to be further proof of the ‘turbulent time’ at hand.

While the depiction of the building with the oversized sword appeared unambitious and, according to Josef Zemp, not reflective of reality, the illustrator spent time on specific details: the crown glass window panes, the folds of the nightshirt worn by the emissary falling down, the scoop wheel and the clothing of the three figures on the bridge.

The Wickiana collection includes further reports of deaths caused by one’s own hand (not for the faint of heart).

![«Von einem leidigen und erschrokenlichen unnfal der sich alhie Zürich am 12 Aprilis […] zum schwert zuogetragen». (Bild: ZB Zürich, Ms. F 28, f. 57r)](https://www.zb.uzh.ch/storage/app/media/uploaded-files/1701878319621.png)

Nocturnal hauntings in the churchyard

The writer claims this night-time incident truly happened in Zurich: bright figures assembled in the Grossmünster churchyard for a dance of death.

The anonymous illustrator captured the ghost for posterity: in the skies, four especially bright stars and the moon join the dance. The detailed architectural design of the Grossmünster seems to support the claim for authenticity. The illustrator carefully depicted the brickwork, the clerestory, the church towers – which still had pointed spires around 1581 – and the earlier outside staircase. He may have used a print as his template.

The Wickiana collection contains other reports of ghost sightings.

Sundowner on the Limmatstein

On 10 February 1585, tanners and butchers spent the evening drinking on the Limmatstein, also known as the Metzgerstein. When water levels were low, a large glacial erratic beneath the Rathausbrücke bridge protruded from the water as a wide slab of rock and, as the drawing shows, offered ample room for a table and benches.

Thanks to the generosity of five citizens and the proprietor of Zum Schwert, the goblets of wine overflow.

Proportions mattered little to the illustrator, but they prized details: the little fisherman’s hut with its fishing traps, the scoop wheel on the Untere Brücke bridge, the buildings by the banks. A tanner works in the water outside the prison.

As the Metzgerstein obstructed shipping, it was largely destroyed in 1823 and fully demolished in 1881 when the bridge was rebuilt.

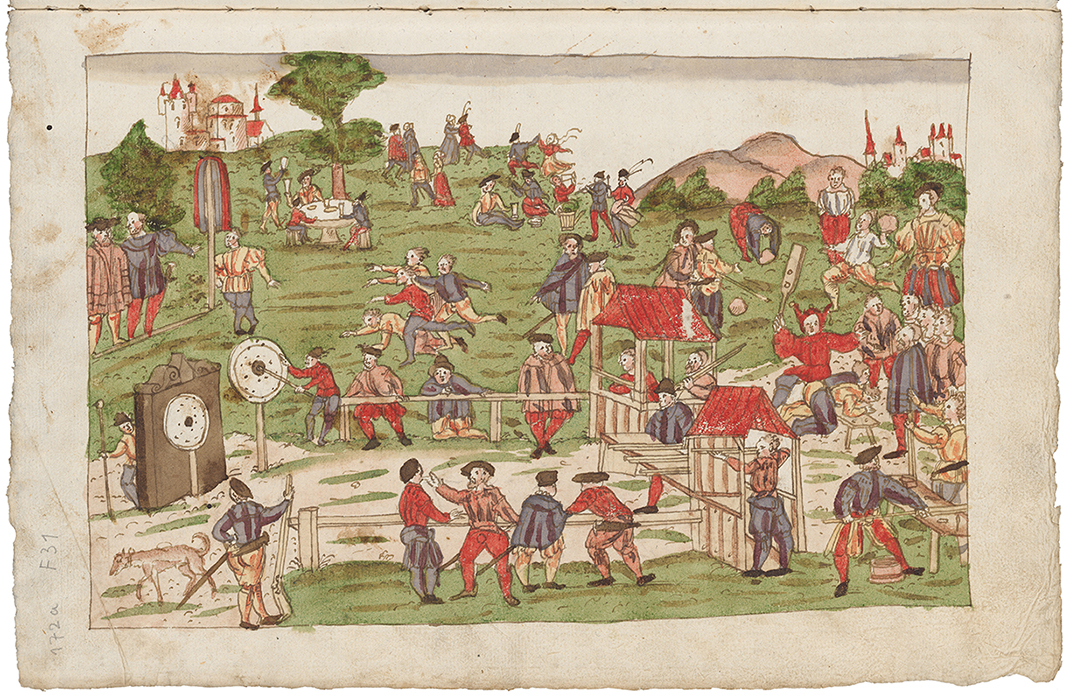

Employment programme during hard times

The whole-page illustration can be found in the second-to-last volume. According to Matthias Senn, its illustrations are particularly valuable from an artistic perspective. The city in the bottom half of the picture may have been based on Jos Murer’s detailed landscape illustration (1576). The roofs are all the same shade of vermilion red.

You can make out the mills and water wheels on the Limmat, and even the well on the Rathausbrücke bridge. The prison tower appears perilously close to the wooden bridge. The illustrator didn’t take the city wall between the Augustinian Church and the Werkhof too seriously, either. He omitted towers and added a surprising central gateway.

Zurich is devoid of people, but there’s a little more action on the mountainside: the route to Stettbach is being extended. During the great famine, road-building on the Zürichberg offered 300 workers gainful employment.

‘Books of miracles’ as a genre

Wick’s ‘books of miracles’, as he himself called them, and his passion for collecting are unrivalled. However, his fascination with extraordinary phenomena, portents and their consequences is part of a larger tradition. Miracles had a role to play back in the Bible, in ancient historiography and in epic poems: the rainbow after the Great Flood, the burning bush, the ten Plagues of Egypt, the Star of Bethlehem and so on.

Wick’s ‘books of miracles’, as he himself called them, and his passion for collecting are unrivalled. However, his fascination with extraordinary phenomena, portents and their consequences is part of a larger tradition. Miracles had a role to play back in the Bible, in ancient historiography and in epic poems: the rainbow after the Great Flood, the burning bush, the ten Plagues of Egypt, the Star of Bethlehem and so on.

Lots of books of miracles were created in the crisis-ravaged 16th century, including the Augsburg Book of Miracles, offering truly surrealist illustrations of 167 strange, fear-inducing occurrences. Wick was doubtless familiar with the drawings of comets and ghosts by Ludwig Lavater, who would go on to be Antiste of Zurich, and the ‘Book of Miracles’ published in Basel in 1557 and written by Konrad Lykosthenes, depicting all kinds of portents since the creation of the world.

Read more – research tips

- Search tool: All the volumes of the Wickiana, along with the individual illustrations, bound-in prints and separate broadsheets, can be researched on swisscollections.ch.

- Digital copies: The 24 handwritten volumes (stored under 25 shelf marks) with bound-in prints and the separate pamphlets can be accessed in full via our platform e-manuscripta.ch.

- Editions: The translations from Latin and transcriptions into modern German used here are by Professor Peter Stotz and taken from the Wickiana edition by Matthias Senn.

- Transcription tool: Help to transcribe all the contents of the Wickiana on e-manuscripta.ch!

- Information sheet: We have put together various pieces of information for you on researching images, topics and digital copies, along with a selection of publications and links.

Monica Seidler-Hux, research team member, Manuscripts department,

October 2023

Header image: Illustration of a celestial phenomenon above the village of Alt-Knin, near Prague, 1580 (ZB Zürich, Ms. F 29, f. 172v)